The Human Crisis of AI Exceptionalism: the case of Diella, Albania’s ‘AI Minister’

The idea that one day machines will replace humans or surpass our intelligence capabilities is not new. It has been permeating the collective imaginaries for centuries, most notably being featured in books, movies, and series, like the iconic HAL-9000. Today, the belief is that this replacement will soon occur through artificial intelligence.

Although experts are well aware of the current powers and limitations of AI, there is a general misconception by the public that AI not only is flawless but also possesses equal or superior intelligence and capacities to humans. Therefore, it is now being tossed around like a magical solution to any issue.

AI Exceptionalism

This belief is actually the foundation for AI exceptionalism. This concept reflects, as described by Dellamary, professor of linguistic anthropology at Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, the idea that AI is a new technology that transcends historical trajectories of tool creation, cognition, and knowledge production.

In simpler terms, the concept is that AI systems are more intelligent and objective than humans, as the former performs fantastic feats of computation, whereas the latter is susceptible to failure. However, as Dellamary rightfully exposes, AI exceptionalism is a myth, at least for now, despite current efforts to achieve a form of AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) within the coming years.

Nevertheless, this recurring theme showcases a crisis in humanity, that is, humans are perceived as inherently flawed and can no longer find better solutions to issues than technology. This is evidenced by the vast increase in AI use worldwide as a means of replacing rather than enhancing human performance, efficiency, and accountability.

It is also this disbelief in our own capacities, aligned with the misconception of an artificial superior intelligence, that leads governments and organisations to look at AI as the solution to all problems—corruption in the present case.

‘AI Minister’: Welcome to Diella!

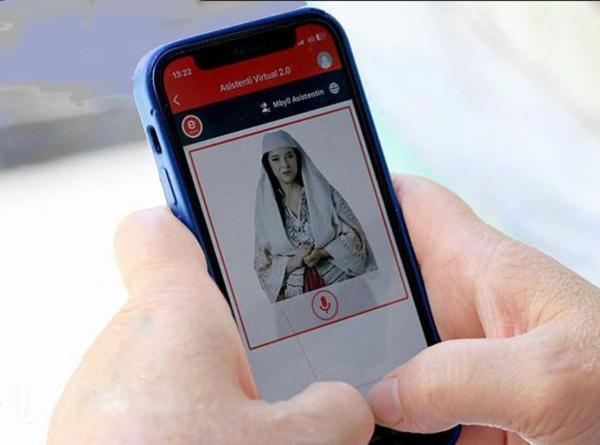

Albania’s Prime Minister, Edi Rama, appointed ‘Diella’ on September 12th, 2025, as a new ‘AI Minister.’ Although your first thought may have been a Minister to oversee AI operations in Albania’s government, in reality, it is quite the opposite: an AI system has been ‘appointed’ minister.

The reason to appoint an “AI Minister” has a simple answer. According to the Prime Minister, Diella will be responsible for ensuring Albania becomes “a country where public tenders are 100% free of corruption”—a major obstacle to Albania’s accession to the European Union, a process officially started back in 2014.

However, her role, as reported by the government official, is not limited to removing every potential influence on public bidding but would also extend to enhancing the public procurement process, making it faster, more efficient, and ‘totally accountable.’

To do so, a team of international experts has been selected to create Diella, the first AI model in public procurement and the first artificial member of Albania’s cabinet of ministers. This move comes as a surprise, considering Albania does not have a clear AI governance framework—a political choice that may underline a certain tone on AI exceptionalism.

The country has not yet adhered to the OECD AI Principles, the first intergovernmental standard on AI globally, nor the Council of Europe Framework Convention on Artificial Intelligence, the first-ever international legally binding treaty on AI, although Albania is a member of this international organisation, mainly devoted to the protection and promotion of human rights across the continent and beyond.

Furthermore, as highlighted by Lufti Dervishi, an Albanian political scientist, there is no information about how Diella will actually work. Is this a ‘true’ minister, as an independent body, a replacement for humans, or is this an AI tool that will assist humans in removing obstacles of the procurement process and increasing impartiality in light of corruption?

AI cannot be vilified. It can be a great asset, a tool, if correctly governed, and Albania’s initiative may be proven one to follow. However, AI is not perfect, and assuming it as the easy solution, without further evaluating its capabilities and potential consequences, is just one more example of AI exceptionalism in effect.

Diella: A symbolic Minister?

Classically envisioned by the Albanian Constitution as a ‘human’ function, the role and powers of ministers have initially appeared to be granted in full to Diella, sparking controversy and leading the Albanian opposition to appeal to the Constitutional Court, primarily over its transparency and accountability.

Amid ‘her’ controversial debut, the Prime Minister swiftly released a decree on September 18th, confirming the PM’s sole responsibility for the ‘creation and operation’ of the virtual minister. It remains unclear, however, whether the newly appointed AI will survive the Constitutional Court’s scrutiny, considering the constitutional provisions on who can be appointed to a public function are clearly directed at human beings, notwithstanding their faculties and merits.

It is also uncertain whether it will comply with the standards of the European Union, which Albania hopes to join within the next five years. If ruled unconstitutional, Diella may no longer be considered an “AI Minister.” Nevertheless, this does not prevent Albania from using it in its procurement process, albeit with the necessary governance scheme and safeguards in place.

But beyond these legal questionings, the very act of appointing an AI as a minister, or even merely granting it public functions, thereby considering the creation of a virtual personhood status, raises several concerns about whether this is a true symbolic act of an AI tool being leveraged to enhance the procurement process or the first step towards a further intrication of AI into core human activities, like policy-making and governance—but void of any accountability nor, in our present case, transparency on the chosen governance scheme. A true first step towards a policy fully embracing AI exceptionalism?

Diella: What to be concerned about?

The announcement of Diella was not only a surprise to AI and privacy academics but also a warning of the risks of falling into AI exceptionalism, raising concerns about its governance, or rather, the evident lack thereof.

AI, as great a tool as it can be, is hardly a human replacement and should not be presented as a magical, flawless solution.

As Dellamary emphasises,

“By reconceptualizing AI not as a rupture but as a magnifier, we can navigate the traps of exceptionalism without falling into complacency. This perspective enables us to recognize that the challenges posed by AI are neither unprecedented nor inevitable but intensified manifestations of persistent social, political, and epistemic dilemmas.”

The primary challenges posed by Diella are quite evident: data quality, transparency and human oversight, and explainability, along with accountability.

Data quality

Born to solve the issue of corruption in public procurement, Diella might actually reinforce it, blindly. Albania, a country currently ranking 80th out of 180 on the global corruption perceptions index, set the fight against this ‘endemic’ issue as one of its top priorities for its accession to the EU, with public procurement being of special interest, as one of the most affected sectors, notably through irregular payments, bribes, favoritism, and patronage frameworks.

Yet, this is the historical data Diella may be trained on—a question to be answered, due to present transparency issues on the matter. As it is widely known, data quality directly impacts AI performance. According to the concept of ‘garbage in, garbage out,’ if poor-quality data (often dubbed ‘garbage’) is put into the training, validation, and evaluation of the system, poor or unreliable decisions will come out in turn. In the present case, tackling the issue of corruption with corrupted data may prove unproductive and unreliable, to say the least.

In short, if the historically available data is not credible, that is, trustworthy in its source and content, according to Khatri and Brown, how can Albania ensure that Diella will not just replicate actual biases?

Transparency and Oversight

Diella was simply announced as the new “AI Minister” without the disclosure of any further information. As established by the OECD AI Principles and the Council of Europe’s AI Framework Convention, AI actors should comply with transparency requirements and provide adequate, meaningful information about their artificial creations, that is, a general understanding of the AI systems, i.e. their capabilities, limitations, and provenance of training datasets. To this day, Albania has yet to clarify all of this information.

Furthermore, there is no clear oversight mechanism in place, despite the requirements established on the matter by said international frameworks. In that sense, AI tools shall be governed, along with all development and implementation steps, by a human who participates in the decision-making ‘loop’. That is, either a human is ‘in-the-loop’ (HIL), being directly involved in the making and approval of decisions at every step of the process, or it is ‘on-the-loop’ (HOL), acting as a supervisor of the AI, only monitoring its process and intervening when necessary. If completely absent, the human is out of the loop.

However, it is not yet possible to ascertain whether Diella will operate independently—human ‘out of the loop’—or will be an assistant tool, in which a human will be the responsible party for reviews, decisions, and/or monitoring—HIL or HOL. The question of whether Diella’s outputs on which projects are awarded in procurement constitute automated decision-making remains equally open. As is the matter of safeguards and monitoring in the likelihood of adversarial attacks and other events that may corrupt Diella’s decision-making.

Explainability and Accountability

Once Diella is deployed, the issues do not go away. In case it reaches a decision, two main concerns arise.

First, according to the OECD AI Principles and the Council of Europe’s AI Framework Convention, Albania should demonstrate the logic employed by Diella to reach its output, that is, explain the process backing the decision-making. Without said information, those affected are not able to challenge it. And consequently, according to said frameworks, there is no clear accountability in the event of an algorithmic decision based on incorrect, false, or biased data that leads to an individual’s or a company’s harm, especially knowledge of who is responsible for eventual compensations.

The mere fact that the Prime Minister would be held accountablefor his ‘AI Minister’s decisions cannot sufficiently clarify the extent to which accountability will be held in practice, as it ignores other potential humans in/on the loop and third-party involvement.

Conclusion

Diella has proven to be, in every angle of the concept, the ‘materialisation’ of AI exceptionalism. An easy solution to a massive problem, without due consideration for the obvious consequences of insufficient steps towards a reliable governance scheme for AI usage. Without such steps, Diella may only prove a typical textbook case for AI implementation by states and organisations alike.

Although artificial intelligence is not anywhere ready to replace humans, it is a powerful tool that shall be used to our advantage, so long as the proper governance is set into place. Current disbelief in human intelligence does not justify removing them from creating and governing solutions to long-standing human problems. For Diella to eventually fulfil its promise, Albania shall recognise that to move forward with innovative technologies, it shall first address the main concerns of data quality, lack of transparency, human oversight and explainability, and a somewhat obscure accountability scheme.

Without human accountability and a truly transparent and reliable governance scheme, Diella risks becoming less a minister and more of a mirror of most flaws of AI exceptionalism.

Martin Démas is a postgraduate law student and scholarship holder in the European Master in Law, Data and Artificial Intelligence (EMILDAI), specialising in data and AI governance. He has worked as a research assistant on online disinformation, environmental law, and AI regulation at DCU and Erasmus University Rotterdam. He holds a Master’s degree in EU law from Université de Tours and studied at Chuo University in Tokyo; he speaks French, English, and German.

Martin Démas is a postgraduate law student and scholarship holder in the European Master in Law, Data and Artificial Intelligence (EMILDAI), specialising in data and AI governance. He has worked as a research assistant on online disinformation, environmental law, and AI regulation at DCU and Erasmus University Rotterdam. He holds a Master’s degree in EU law from Université de Tours and studied at Chuo University in Tokyo; he speaks French, English, and German.

Luisa Maciel Perez is a Brazilian-qualified lawyer currently pursuing the European Master in

Luisa Maciel Perez is a Brazilian-qualified lawyer currently pursuing the European Master in

Law, Data and AI (EMILDAI), specialising in data and AI governance. She has worked in

major Brazilian law firms and international research organisations, including ADAPT

(Trinity College Dublin), the Privacy & Access Council of Canada, and Lawgorithm. She is a

CIPP/E and CIPM holder, active in the Center for AI and Digital Policy (CAIDP), and speaks

Portuguese, English, French, Spanish, and Hebrew.

Originally published on 03OCT2025 at EMILDAI