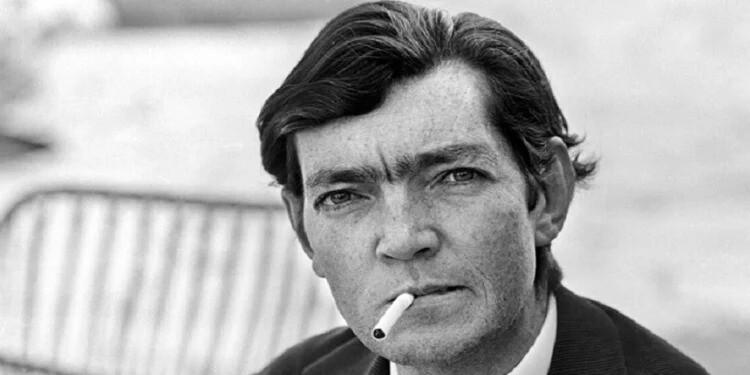

Julio Cortazar: A Pampered Leftist Writer Who Indulged Dictatorships In Cuba And Nicaragua

Cortazar, despite being a poet and novelist, never criticized censorship, imprisonment of dissidents, or summary executions carried out by pals such as Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

The Argentine author Julio Cortázar made himself a man with a restless conscience walking a tightrope while always having a net to catch himself. He wrote brilliantly when he felt like it and fought enthusiastically for causes that did not require him to pay a price.

He was born to Argentine diplomat parents on August 26, 1914, in Brussels. In 1951, he emigrated to France, where he spent most of his life as a lionised intellectual. This European journey explains a lot about the character of an intellectual who spoke of revolution but from a comfortable home, while denouncing oppression from cafés where wine and favourable press were never in short supply. His political shift has a specific date and is not innocent.

In the early 1960s, he fervently embraced the Cuban narrative. He visited Havana frequently, joined the regime's cultural circuit and applauded the revolution as one would approve of a play. In 1963, he published his novel, Rayuela, which in its English translation is known as Hopscotch, and became a beacon for his generation. With that symbolic capital, he supported the murderous Fidel Castro when there was already censorship, firing squads, and political prisoners. The writer who played at breaking literary structures did not want to break the structure of Cuba's unitary party. That is where his complicity began. While the poet Heberto Padilla was detained, humiliated and forced into humiliating acts of public self-incrimination, Cortázar opted for a lukewarm equanimity. He signed critical letters but was careful not to break with the powers-that-be. Later, in 1974, he accepted the Médicis Prize in France and donated the money to Latin American left-wing causes, a much-heralded gesture that did not cost him imprisonment or forced exile.

His relationship with Nicaragua confirms the pattern. He applauded Sandinismo after 1979 and celebrated revolutionary poetry while the new power elite shut down the media and concentrated their control. When reality turned ugly, he returned to metaphor. Cortázar loved revolution as an aesthetic idea. But when it came to revolutionary clamp-downs by police, he looked the other way.

On a personal level, his emotional life was a series of relationships with women where the imbalance of power was not just anecdotal. His marriage to his second wife, Carol Dunlop, was marked by dependence and illness, and ended in tragedy when she died in 1982. A Canadian, Dunlop was a writer, translator, and activist. She and Cortazar were the co-authors of the book The Autonauts of the Cosmoroute. It has been theorised that both of them suffered from HIV infection. Following her death, Cortázar followed her just two years later.

The left canonises him for Rayuela and for his playful tone that seemed subversive. What the leftist narrative does not mention is his sustained silence in the face of real repression. He never consistently denounced the

Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción (UMAP), or Military Units to Aid Production, was an archipelago of forced-labour concentration camps operated by the Cuban government from 1965 to 1968. Designed to "re-educate" non-conformists, believing Christians, and "anti-social" elements, these camps held an estimated 25,000 to 35,000 people, including homosexual men, intellectuals, and political dissidents. Nor did he criticize Cuba's systematic censorship, or the imprisonment of Cuban dissidents. He preferred elegant ambiguity, the kind that allowed him to return to Paris to applause and return to Havana by invitation. When he returned to Argentina for the last time, when democracy was restored in 1983 after a decade of military dictatorship, newly elected President Raúl Alfonsín refused to receive him. Cortázar died on February 12, 1984, in Paris, as a French citizen

If Cortázar had to live in today's Cuba, without cultural credentials or a return ticket, the game of hopscotch would end very quickly. Amidst blackouts, queues for food and medicine, and neighbourhood snitches, Cortázar's sort of literary games would not last long. Metaphors cannot be used to buy rice, and tightrope walkers like the cosmopolitan Cortazar end up falling hard when the floor is made of cement, as in a prison cell. There, he would have discovered that the revolution he loved as an idea does not tolerate those who ask too many questions, and that the silence of intellectuals also weighs heavily when history reviews the past.