Latin Is Not A Dead Language: It's A Controversial Tongue

How 'Latin' has been defined has changed over the centuries.

Dead languages, extinct languages, languages with no native speakers, etc: all of these are terms that vary from one expert to another in discussions among linguists, especially regarding Latin.

In reality, Latin should not be considered a dead language because it continues to be used as a lingua franca (a language used for communication, spoken quickly and poorly), even if only in a few very small circles, such as the Catholic Church, especially in its liturgies.

Latin was, of course, spoken in Antiquity and has been passed down in work written by Gaius Julius Caesar, Seneca, and Virgil. This is the language of schools where Classical education is still revered, differing as it does from later ecclesiastical Latin. And it was a language spoken on the streets of Europe for many centuries. And to the surprise of some, as we move forward in time and beyond the first centuries of the Christian era, there are more and more texts in Latin. Indeed, there were more texts produced in the 7th century than in the 1st century. They are more recent and have survived better.

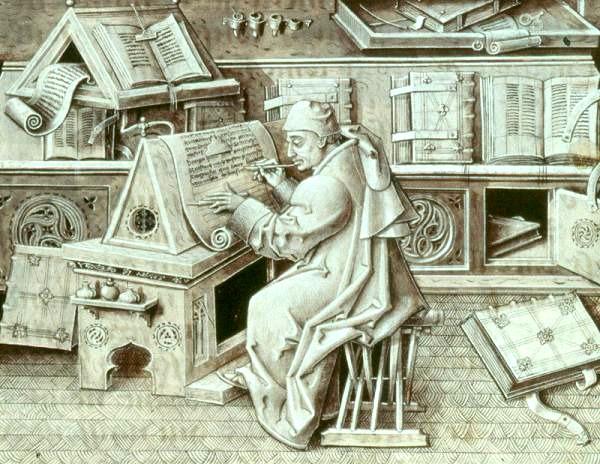

In the Middle Ages, in addition to its continued literary use, Latin became the official language of the chancelleries of the medieval kingdoms, which wrote everything in Latin (at least for a time), as well as the language of the Church. Universities, for their part, also favored the use of Latin in the classroom because the books were in Latin. This language was used for class discussions, and, in short, for academic purposes. It was also the language of administration and diplomacy throughout Western Europe in medieval times.

In the Middle Ages, Latin and Christianity unified Western and Northern Europe. When we refer to the Middle Ages, in fact, the term Latin Europe refers to Catholic Europe, whose language of culture and worship was Latin, as opposed to Greek of the Byzantine east, which, after the Great Schism of 1054 AD, became Orthodox. Slavic Europe (mostly also Orthodox, although with many parts that were also considered part of Latinitas) also eschewed Latin. In other words, when we say Latin Europe in a medieval historical context (and beyond, up to the Protestant Reformation, in fact), Scandinavia, the British Isles, and Germany are also included.

The word ‘Latin’ has changed meaning throughout history and, in fact, has meant and still means many things; it does not have a fixed, static meaning and does not need or have to mean anything specific. For example, the lands south of the United States continue to be called ‘Latin’ America, in tribute to the predominance of Portuguese and Spanish speakers: the inheritors of Latin Iberia.

The meaning, as with any other word, is given to it by us through use, whether in its popular variant, in standard language, or in some technical use in the social sciences. We all like the word ‘Latin’ very much, and we all want to use it in our own field, but the only empirical reality is this: its meaning has changed greatly and it currently means many things.

But the golden age of Latin, and also the period that marked the onset of its decline, was the Modern Age. During the 16th century, at the height of Humanism and the Renaissance, and then during the 17th and 18th centuries, more texts were written in Latin than during the entire Ancient and Medieval periods combined (or at least, those that have survived to this day).

Not only were enormous numbers of texts produced, which also reached many more people (thanks to the printing press), but Latin itself changed. Humanists despised medieval Latin because they considered it impure and full of defects (remember that the language was not viewed from a scientific perspective until the 19th century), so they took it upon themselves to write in a purer form of Latin, which, for them, meant closer to the Latin of the Romans, the classical Latin of the 1st century.

At the end of the 17th century, two significant events occurred: first, the Treaty of Westphalia, and then the Peace of the Pyrenees, which made France the leading European power. And so, little by little, very little by little (at the end of the 18th century, while there were still those who considered learning Latin to be essential, and in the 19th century, a large number of doctoral theses in Germany were still written in Latin), Latin began to lose its influence, becoming less and less common in more and more areas, mainly to be replaced by French and, later, English.

Latin has seen a revival, however, among Catholics seeking a more traditional form of worship in what has been dubbed the Traditional Latin Mass. Again, the language has become controversial, and has been banned from liturgies by some Catholic prelates.

Why the Catholic Church abandoned Latin in its liturgy in the West, and was left behind by Western elites, is another story.