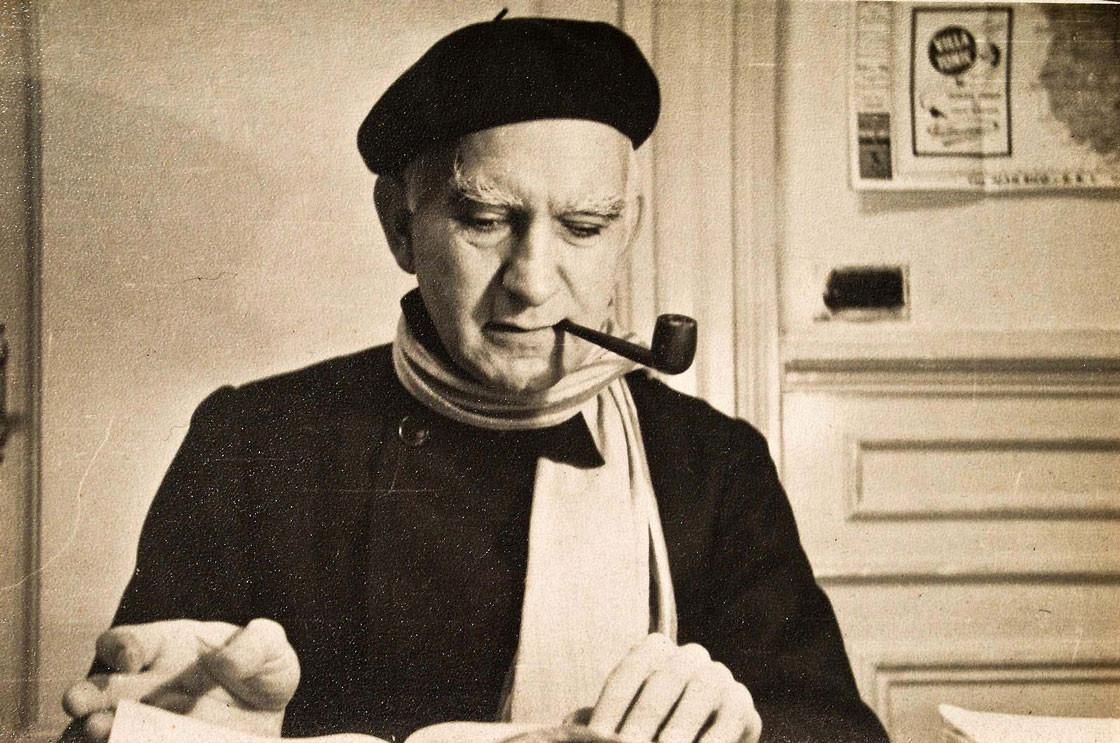

Leonardo Castellani: An Irascible Witness To Christ

Once suspended from his priesthood, Fr. Castellani was a witness to his faith and to the perfidy of fellow clergymen.

Leonardo Luis Castellani Contepomi was born on November 16, 1899, in Reconquista, a city in the semi-tropical province of Santa Fe in northern Argentina. At the time of his birth, European settlement in the region was still recent, and memories remained vivid of conflicts with native tribes who raided ranches and farms, rustling cattle, and killing settlers. His father, Luis Héctor Castellani, was an Italian immigrant who spent most of his life in Argentina, while his mother, Catalina Contepomi, was an Argentine of Italian parentage. Castellani’s paternal grandfather, also named Leonardo, was an Italian architect and one of the founders of the village of San Antonio de Obligado in Santa Fe, where he built eleven churches.

Castellani’s father was a teacher and journalist who founded El Independiente, the first newspaper in the arid Chaco region of Santa Fe. An activist in the Radical Civic Union party, he was murdered in 1906 by local police acting under orders of the provincial governor, when Castellani was five years old. During his childhood, Castellani also lost an eye, which was replaced with a prosthetic. He would later take up the pen left behind by his father, excel in his studies, and enter the Jesuit novitiate in 1918. His academic brilliance was soon recognized.

In Córdoba, Argentina’s third-largest city, Castellani studied literature before moving to Buenos Aires, where he taught Spanish and Italian language and literature, as well as history, at the Colegio del Salvador, the country’s leading Jesuit preparatory school. It was there that he began writing portions of Camperas: Bichos y Personas, a collection of fables first published in 1935 and still in print.

Castellani began his theological studies at the Metropolitan Seminary in Buenos Aires but was sent to the Gregorian University in Rome in 1929. There, his formation flourished under the tutelage of Cardinal Louis Billot and was influenced by Georges Dumas, Joseph Maréchal, and Marcel Jousse. He pursued doctoral studies and was ordained to the priesthood as a Jesuit in 1930. Two years later, he traveled to France, where he remained for three years. During this period, he studied psychology at the Sorbonne and is believed to have received a petit doctorat in 1934. He observed patients—especially children—at various sanatoria and traveled throughout Austria, Germany, Italy, and England. Castellani became deeply familiar with English, French, German, Greek, and Latin literature, and later learned Danish in order to read Søren Kierkegaard in the original.

Returning to Argentina in 1935, Castellani entered an exceptionally productive period of teaching and writing. Over the next eleven years, he published twelve books and numerous essays on political, religious, and cultural topics in publications such as Cabildo, Criterio, La Nación, and Tribunal. His works from this period included a translation of part of the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas; Historias del Norte Bravo; Martita Ofelia y otros cuentos de fantasmas; Las muertes del Padre Metri; Las canciones de Militis; Crítica literaria; and El nuevo gobierno de Sancho.

Following the Second World War, during which Argentina remained largely non-belligerent, Castellani ran unsuccessfully for a seat in Argentina’s Congress amid political turmoil that culminated in the rise of President Juan Domingo Perón. In 1946, Castellani’s relationship with the Jesuits began to deteriorate, particularly after the publication of Cartas Provinciales, in which he advocated for reform within the order. When his superiors encouraged him to leave, he traveled to Rome to explain his position to Fr. Jean-Baptiste Janssens, the Superior General of the Jesuits.

Suffering from diabetes, chronic insomnia, and declining health, Castellani was sent to Spain and confined to the Manresa retreat center near Barcelona. He left Manresa without permission and returned to Argentina in 1949. In October of that year, he was expelled from the Society of Jesus and suspended from the priesthood a divinis, barred from administering the sacraments or celebrating Mass—a decision reserved to the Pope alone. He was denied a canonical trial and was never informed of the charges against him. In middle age, Castellani was left penniless and dependent on his siblings. Denied even the right of appeal, he later used his ordeal as material for his novels, dramatizing accusations made against him by fellow clerics. According to his biographer Sebastián Randle, records of the accusations and correspondence remain sealed in a secret archive in Buenos Aires.

In his conflict with Jesuit authorities, Castellani can be compared to Francesco Forgione, later known as Saint Pio of Pietrelcina. Like Castellani, Padre Pio suffered from severe health problems and endured persecution from ecclesiastical authorities. Jealous of the friar’s reputation for sanctity, Bishop Pasquale Gagliardi and members of his diocese, for example, inundated the Vatican with accusations against him. Much of this “veritable satanic war” has been documented in Il Calvario di Padre Pio by Emanuele Brunatto. In both cases, clerical hostility was marked by a troubling degree of pharisaism.

Psychologically and spiritually traumatized by what he perceived as persecution by pharisaical clerics, Castellani turned again to writing, publishing two books within twelve months. His experience of clerical injustice profoundly shaped his later works and the remainder of his life. Many years later, Fr. Javier Olivera Ravasi described Castellani as “a discomfiting prophet,” noting his incisive humor and persistent diagnosis of decadence within both Church and nation. Fr. Olivera Ravasi observed that Castellani believed the spiritual and intellectual formation of priests was already in decline in the 1930s. In some of his novels, Castellani aired his travails in fictionalized form, having been denied a hearing of accusations against him and an opportunity to defend himself.

In 1953, after years spent traveling in Argentina’s interior, Castellani settled permanently in Buenos Aires. There, living alone in an apartment subsidized by friends, he described himself as an “urban hermit.” During the 1950s, his literary output intensified. He published El apokalipsis (sic) de San Juan, ¿Cristo vuelve o no vuelve?, El ruiseñor fusilado / El místico, Los papeles de Benjamín Benavídez, El evangelio de Jesucristo, Las parábolas de Cristo, and Su majestad Dulcinea.

After more than a decade of suspension, Castellani celebrated Mass again in 1962, and then was fully restored to the priesthood in 1966. He, however, declined to rejoin the Jesuits. During the 1960s, he focused primarily on religious writing but also produced novels, poetry, detective fiction, essays, and newspaper articles, while teaching at the university level. By this time, he had withdrawn from politics. In a 1977 interview, he stated, “I’m not a nationalist because I have never wanted to enter politics. I don’t understand it.” He later wrote, “It was then that I suddenly discovered my second vocation, which is as follows: to write good books for God, beg alms for their publication, and give them to Argentina.”

Castellani’s critiques of fellow clerics often verged on polemics but were rooted in his understanding of pharisaism as a corruption of the priestly vocation. In Cómo sobrevivir intelectualmente al siglo XXI, edited by Juan Manuel de Prada, Castellani is quoted as saying: “It would be necessary to be able to see from here (and it is impossible) why a part of the admirable Spanish people … suddenly began to hate God, viciously wish to destroy God—that is to say, priests, monks, temples, chalices, crucifixes, images; the earthly images of God. (…) We would have to talk about Pharisaism, about that subtle disease of the religious instinct called Pharisaism.” Castellani eventually went so far as to call for the suppression of the Jesuits and authored Christ and the Pharisees. Several of his works contain autobiographical elements through which he processed his conflicts with Church authority.

Castellani was sharply critical of both communism and liberalism. In Pluma en ristre, he wrote: “Communism is a great evil, not only because of the plunder and destruction of property, as La Prensa emphasizes, but also because of the destruction of the human person and the soul. It is terrible that communists burn churches and kill Christians. But it is equally terrible that liberal governments blithely tolerate the exploitation, corruption, and de-Christianization of the poor. If you were to ask me which of the two is worse, I would say that, sub specie aeternitatis, the second is more terrible—among other things, because it is the cause of the first.”

As Castellani entered his eighth decade, Argentina descended into political chaos. Juan Perón returned to the presidency in 1973 and died the following year, leaving power to his wife, Isabel Martínez. Political violence escalated until the military coup of 1976 ushered in the period known as the Dirty War, during which as many as 30,000 people were tortured or murdered. Those abducted by the regime became known as the “disappeared.”

Among them was the leftist writer Haroldo Conti. His partner, Marta Scavac, appealed to Jorge Luis Borges, Ernesto Sábato, and Castellani to intercede with dictator Jorge Videla. Scavac later recalled visiting Castellani’s apartment, where he lived “in absolute poverty.” “I knelt before him to implore him to help me save Haroldo,” she said. “He sat down on his bed with difficulty, put his hand on my head, and gave me his word that he would do what he could.” Castellani met with Videla, identified Conti as his former student, and later visited him in prison, where he found him beaten and unable to speak. Conti was never seen again.

Around this time, Castellani was visited by his biographer Randle, then a high school student, who described the elderly priest as “irascible” toward bourgeois Argentines but notably gentle and attentive toward the poor. Randle recounted the case of a woman who brought her violent, troubled son to Castellani. Castellani took the boy into his care for a week. The child was transformed, later excelling academically and becoming a physician. His mother regarded the change as miraculous.

From the late 1970s until he died in 1981, Castellani’s health declined, and his writing slowed. Friends paid his rent and medical expenses. In a 1980 interview, the agnostic journalist Rodolfo Braceli asked whether he feared death. Castellani replied: “I don’t think much about it … but sometimes I ask myself how it will come to me.” When asked whether this reflected fear or curiosity, he answered: “It’s more curiosity than fear, even though I recognize some fear. It is something very definite—death—quite radical.”

When asked if he had anything more to say, Castellani responded: “The same thing I wrote when I shut down Jauja. If there is forgiveness for telling the truth, even when telling it is dangerous, may God forgive me. But since I have one foot in the grave, what else can I do but tell the truth? That will be my final penance. That is how I prepare for a good death.” On March 15, 1981, under the care of Irene Caminos, Castellani collapsed after lunch in his small apartment. Assisted to his bed, his final words were: “I surrender.”

Castellani retains a small but fervent following in the Hispanic world. Argentine missionaries in some of the most remote and dangerous places on earth—Afghanistan, Siberia, Bhutan, and Malawi—consider his Camperas nearly as essential as a Bible and breviary. Among his admirers was Cardinal Antonio Quarracino, who ordained Fr. Jorge Bergoglio, the future Pope Francis. Never afraid of controversy, Castellani engaged politics, literature, and religion with equal intensity. Despite misunderstandings, opposition, and polemics, his faith remained unshaken. It may truly be said of Leonardo Castellani that he fought with everyone—except with God.