A Man Of Iron Vetoed Taxpayer Funded Fourth Of July

If America ever falls into financial ruin, one reason will be that we stopped electing men like Grover Cleveland.

When the city council of Buffalo, New York, sent the mayor a measure to fund Fourth of July celebrations in 1882, conventional wisdom suggested that approving it was the politically wise and patriotic thing to do. After all, the money would pay for festivities planned by the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a very influential organization of Civil War veterans.

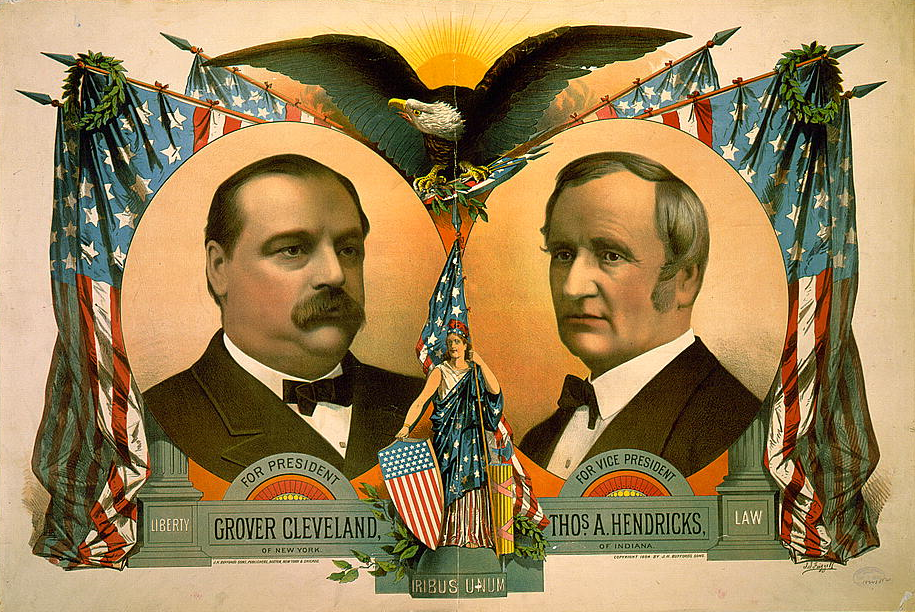

The conventional wisdom underestimated the mayor. He vetoed the appropriation, and proudly took the heat for it. After a year in the job in which he earned the title, “the veto mayor,” he moved on to become “the veto governor” of the State of New York and finally, “the veto president” of the United States. His name was Grover Cleveland. On the matter of minding the till and pinching pennies on behalf of the taxpayer, he puts to shame the great majority of public officials here and everywhere.

In his recent biography titled A Man of Iron: The Turbulent Life and Improbable Presidency of Grover Cleveland, Troy Senik recounts Grover’s message explaining the veto:

[T]he money contributed should be a free gift of the citizens and taxpayers and should not be extorted from them by taxation. This is so because the purpose for which this money is asked does not involve their protection or interest as members of the community, and it may or may not be approved by them.

This was a man unafraid to draw the line on public spending for two principal reasons:

1) Government should not be a grab bag of goodies for whatever cause somebody thinks is “good” and

2) Failure to keep government spending in check encourages politicians to buy votes and corrupt the political process.

That all sounds quaint and frumpy in these enlightened times of trillion-dollar deficits. Even more out-of-step with current fashion is what Cleveland did as soon as he issued his veto. Senik reveals,

Cleveland made a personal donation equal to 10 percent of the GAR’s budget request, then deputized the president of the city council to help raise the rest through private funds. In the end, the organization raised 40 percent more than it had requested from the city treasury.

Personally, Grover loved pork in his sausage, but he hated it in bills. He once expressed the wish that he would be remembered more for the laws he killed than the ones he signed. He still holds the record for the most vetoes of any American president in two terms (584 in all).

Back in Buffalo where his impressive veto record began in 1882, Cleveland barbecued public pork like every day was the 4th of July. Allan Nevins, who won a Pulitzer for his masterful 1948 biography of him, writes that Cleveland “kept up a constant fire” of vetoes:

He vetoed a gift of $500 for the Fireman’s Benevolent Association. He vetoed bills for unnecessary sidewalks, [and] for the unnecessary notices of tax sales…He refused to be good-natured about small matters. He would not wink at little devices for getting public work done without competitive bids, and he had a blunt way of calling attention to all sorts of abuses.

During his first term in the White House, he was cautioned to lie low and take it easy on controversial issues. He responded, “What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something?”

If America ever falls into the crevasse of financial ruin, one reason will be that we stopped electing men and women like Grover Cleveland.

Happy 4th of July!

Lawrence W. Reed writes for the Foundation for Economic Education.