A Journalist Reflects on Covering Euthanasia

Journalism is at its best in the midst of conflict.

There are few subjects as divisive and traumatic as euthanasia.

My agencies have covered numerous stories over the years and it would be fair to say that the activities of Dignitas, the Swiss euthanasia clinic, are featured more often than anything else.

The vast majority of the articles were critical, putting their philosophy under the spotlight, and dissecting them on the pages of a swathe of international publications.

Journalism is at its best with conflict, and the articles were constantly challenging whether it was right for Switzerland to help other people to die, something that was in most cases illegal in their own homelands.

It was claimed in one of the last stories I wrote about my old nemesis Ludwig Minelli — the now 89-year-old Dignitas founder — that he had made millions from death. And, whether true or not, with our journalism it was not an easy path.

Our reports were published in the Times, Telegraph and Observer, and from the British Medical Journal through to the Sunday Sport, a ‘newspaper’ that could never publish a story without at least two semi-naked women on each page.

I have little doubt that this broad spectrum of coverage played a major part in the huge number of clients from around the world that sought out Minelli’s services, including more than 300 from the UK, and the numerous personal stories that emerged on the back of that encouraged debate on exactly where do we stand as a global society on euthanasia?

How do we balance the right to life?

Should we spend a million on a drug that will cure a disabled baby when it could be spent elsewhere, and how do we define “elsewhere”?

If we accept euthanasia for the elderly, how old do they need to be?

Do we accept it for the terminally ill, and what about people who just have poor health or extreme pain, but might live many more years? And what about the mentally sick or disabled?

To even raise the question is increasingly a challenge for the media, especially as they move towards giving their audience what they want to hear, and not what they need to hear, not to mention privacy and the rights of those personally confronted with what is one of the last taboos.

The debate over euthanasia is growing, but we rarely cover it following a barrage of criticism over-reporting we did on the case of Noa Pothoven.

We published the following reply to the critics that was completely ignored, but three years on and it seems many of the issues that we tried to raise are still no closer to being solved.

This story is republished from the line site VT that first carried it in 2019, and is a look a how the media in general, and one of my agencies in particular, covered one of the most tragic of euthanasia stories:

Republished here with the permission of VT.

How Fake News Claims Dominated Reports Of Tragic Dutch Girl And Ruined Chances To Learn Real Lessons From Her Death

Story By: Koen Berghuis, Sub-Editor: Joseph Golder, Agency: Central European News Published Date: June 6, 2019

Dutch teenager Noa Pothoven died in a hospital bed, surrounded in her last days by friends and family who accompanied her on her final journey. Also present were doctors who were there to ease her suffering.

There is no argument that this is a tragic story, but there is also no argument that it is an important public interest story that needs debate, and the circumstances surrounding the reporting raise issues that illustrate the pitfalls the media faces in covering such sensitive subjects.

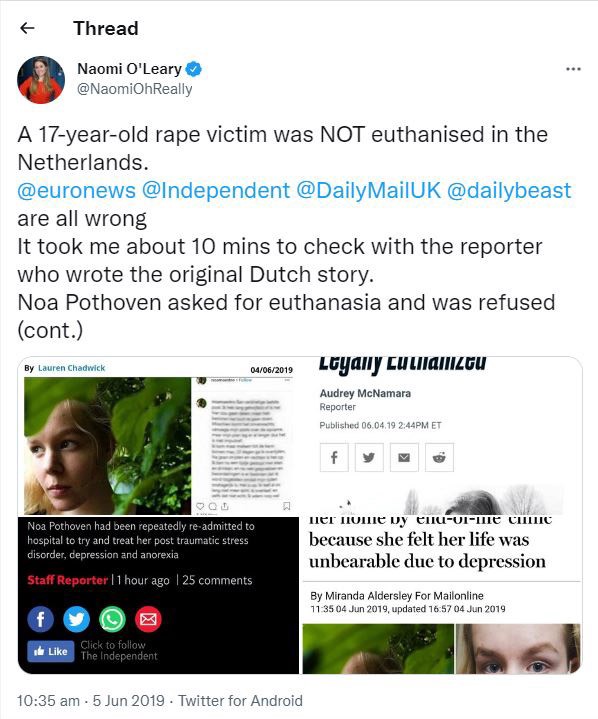

Naomi O’Leary reveals it was not euthanasia after 10 minutes of research.

The story was difficult from the start on many more levels than usual, as normally there would be experts that would comment, maybe organisations or officials involved, yet understandably, those directly involved in this were not allowed to talk. That is not just because of privacy, but also because of the duty of patient doctor confidentiality. In addition, other experts not directly involved were reluctant to speak without knowing the precise details, which were still sketchy at this point.

But in the end the question of how to categorise her death was decided not by experts, or officials, or even doctors because they were not allowed to speak. It was decided in 10 minutes by a journalist calling another journalist and selectively quoting what they said.

A former Reuters reporter called Naomi O’ Leary, in a Twitter post retweeted thousands of times, ‘revealed’ that it was categorically not euthanasia, and then included screenshots from our story on the MailOnline, among others, as examples of those that had got it wrong.

She wrote: “A 17-year-old rape victim was NOT euthanised in the Netherlands. @euronews @Independent @DailyMailUK @dailybeast are all wrong.”

She then said: “It took me about 10 mins to check with the reporter who wrote the original Dutch story. Noa Pothoven asked for euthanasia and was refused (cont.)

“Infuriatingly, it’s too late: this misinformation has already spread all over the world from Australia to the United States to India. Her name, #noapothoven is even trending in Italy.”

She made her posts after speaking to a Dutch journalist called Paul Bolwerk, who she said had repeated what he had already written in his articles.

Based on what he told her, she wrote:

“A decision to move to palliative care and not to force feed at the request of the patient is not euthanasia.”

And she continued:

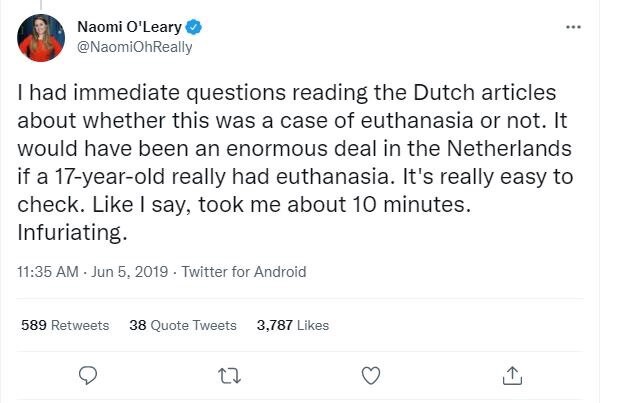

"It’s really easy to check. Like I say, took me about 10 minutes. Infuriating. If you ever worry about whether you can trust a story or not, a good way to check is to look up whether @Reuters is reporting it or not. I trained to be a journalist with @Reuters, this is what they do.”

For the record, calling to ask a reporter and then writing what they say is not what Reuters do. In a case like this you need to reach out to the family or their representatives, as well as their friends, the doctors and organisations involved, and to the prosecutors and police. She apparently did none of those things.

What she did do was criticise others for doing the same as her and simply asking another journalist. In her posts, when other media reached out to ask for a contact for the Dutch reporter, she tweeted: “This is ridiculous. I’m not going to hand out someone’s mobile number. Don’t ask me anymore and do your own reporting.”

But calling another reporter herself was OK, and selectively quoting what they said, and then claiming “it took me about 10 minutes” to get the real story was also OK.

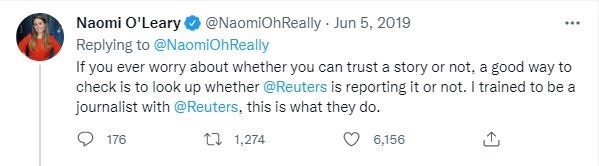

She later shared her version of the story, which was over a thousand words and still appeared not to have spoken to anyone other than the journalist Paul Bolwerk. Interestingly, he did not actually say that it was not euthanasia, what he said was: “No no no no, you can’t speak of active euthanization.” But he did not refer to euthanasia alone, legal or otherwise.

Our attempt to explain from our side in more detail exactly why this was a crucial difference was sent out the same day as Naomi’s social media posts were going viral, and by then the world had already made up its mind.

The matter had already been decided in the pages of big hitters like the Guardian, which Naomi hailed as the proper way to do journalism. She wrote: “Fair play to those who did their job. Here’s an example of a well-reported story on this by @jonhenley at the Guardian. He has checked with the end-of-life clinic, and links to a statement they put out to clarify that Pothoven did not die of euthanasia.”

The End of Life Clinic (Levenseinde) she referred to is based in The Hague, and was the organisation that the Dutch teen Noa had reached out to for euthanasia when she was 16, and been refused.

The End of Life Clinic is a network of facilities affiliated with the largest Dutch euthanasia-advocacy organisation and yes, they did put out a statement, but it was NOT their statement. What they actually said when contacted by the Guardian was the same thing they told us, namely. That “it could not comment for privacy reasons”.

Instead, they had released the statement on behalf of Noa’s friends, so not her doctors, and not her family. It said: “To stop her suffering, she stopped eating and drinking.” The friends added that they did not regard this as euthanasia.

When our Dutch journalist filed his initial breaking news story, he correctly reported that she had been treated by doctors who were present and had eased her passing, and that she had died in a hospital bed. Her family had been aware and prepared for her death, as had the police, and indeed the police confirmed they were not investigating the death, so it had not been illegal.

In his feedback at the time our reporter explained: “I double checked it from original Dutch and can verify the statements. As you can see, nowhere is there any talk of ‘suicide’ in the statement of Noa’s friends, nor in those of her parents or the life-ending clinic (Levenseindekliniek). There is only indirect euphemisms being used such as Noa “stopped eating and drinking” (Levenseindekliniek statement) and “Noa had chosen not to eat and drink anymore” (her parents in a statement).

“Two newspapers writing after our coverage seemed to concur by saying that Noa’s death was ‘guided’ by a medical team present at her home. These two papers are De Telegraaf (the country’s largest) and De Gelderlander (local daily from Noa’s region which initially ran the story. I quote ‘The family Pothoven finds it most regrettable that it was suggested in foreign media that their daughter Noa died through active euthanasia. Noa died Sunday after she stopped eating and drinking. She was being guided by a medical team’.”

He referenced the original Dutch paragraph: “De familie Pothoven betreurt het ten zeerste dat in de buitenlandse media wordt gesuggereerd dat hun dochter Noa overleden is door actieve euthanasie. Noa overleed zondag nadat ze was gestopt met eten en drinken. Ze werd begeleid door een medisch team.”

A screen shot from one of the many international news organizations that built a story around Naomi’s claims.

He pointed out that the Dutch verb ‘begeleiden’ which was used in the reports means “guiding/accompanying/supervised/assisted” in English, with all being acceptable translations. And he noted:

“It leaves quite some room for interpretation, the Dutch verb also leaves a lot of room for interpretation as to which extent the medical team gave in terms of care and what they exactly did on the spot. I think it is also noteworthy that it reads that their daughter did not die from ACTIVE euthanasia (emphasis mine).”

So based on the fact that none of the Dutch media mentioned suicide and doctors were involved while the police who would have investigated a suicide were not, he concluded that indeed what happened was not suicide, and was therefore something else. He decided that something else was euthanasia. And as prosecutors and police were not investigating, and it was not illegal, he concluded that the form of euthanasia that had occurred was ‘legal’.

The logic behind it is clear, but in hindsight, despite clarifying the way she died through thirst and starvation in his report, 90% of people reading it would assume that she had been given an injection or similar in a process we now know is referred to as “active euthanasia”.

Despite qualifying right from the start that she died from refusing to eat or drink, and never mentioning “active euthansia” in our report, within hours the story had moved on from what lessons could be learned from Noa’s tragic death to how had the world’s media got the story so wrong, and in particular, how had we got the story so wrong.

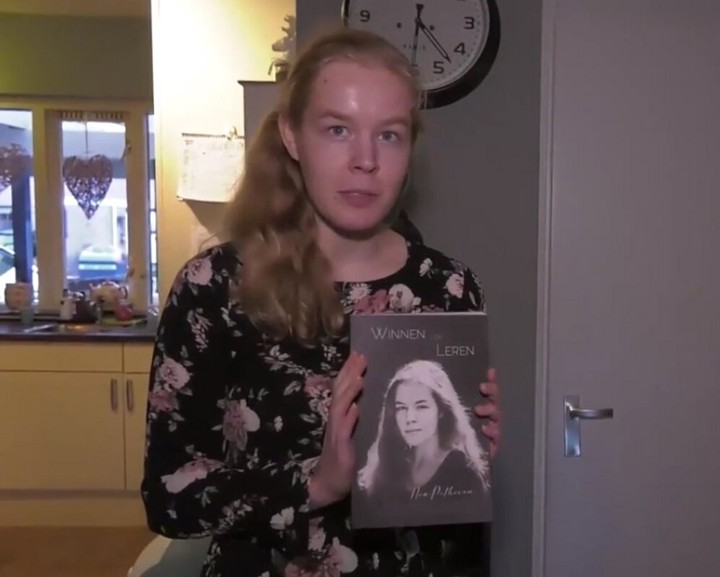

Pic shows: Noa and her mother, who according to her “has always been there for me”

Criticism of the Dutch health service where Noa’s parents complained that she had failed in their duty of care to their daughter was sidelined with the agenda now dictated by a single social media thread. Naomi had published that thread, and her later 1,000 word story, based on an interview with a journalist that took “10 minutes”. Our response took hours, and by that time, no one was listening.

As mentioned, we had spoken to the police and we went back to them again. There was no report of a suspicious death, despite the fact that she had announced her upcoming death, implying that it had been carefully planned in order to make sure it was legally carried out. If it had been suicide there would also have been problems for relatives and indeed medics who would have faced awkward questions, or possibly themselves made a police complaint. Neither happened.

We reached out to Noa’s psychiatrist Roland Verdouw from the Pluryn mental health centre who wrote the foreword of Noa’s autobiography called ‘Winning or Learning’ about her battles with mental illness. Verdouw was not allowed to say if the clinic had given Noa any advice that might have helped her with her planned death. Pluryn spokeswoman Marian Draaisma also could not answer any questions due to patient confidentiality. And as we said, Elke Swart of the End of Life Clinic (Levenseinde) also refused to comment to us other than later offering the statement from her friends.

When Naomi wrote her story in Politico, she revealed that the journalist that had told her it was not euthansia, when what he had said was that it was not “active euthanisation.” And again, as we were finding, active euthanasia is one thing, but there were also many other categories of euthanasia that were also legal.

We discovered psychiatric euthanasia, where psychologically the person no longer wants to go on, but people we spoke to were divided as to whether this involved doctors ‘actively’ helping an otherwise physically healthy person to die on the one hand, or on the other allowing them to take their own life and simply easing their suffering as they did so.

Scott Kim, a psychiatrist and philosopher who studies the subject, was quoted in the Atlantic as saying: “It is not easy to distinguish between a patient who is suicidal and a patient who qualifies for psychiatric euthanasia, because they share many key traits.”

At the time of Noa’s death, most cases of psychiatric euthanasia involved women, and most were administered by the End of Life Clinic.

Pic shows: Noa Pothoven

Our conclusion, in the end, was that the best version to describe what had happened to Noa was actually detailed in a Dutch guide on killing yourself that clearly placed what happened to her in a legal grey zone best described as “self-euthanasia”.

A search online indicates that there is also a booming online presence advising people how to kill themselves legally and describing it as “self-euthanasia”.

In the Netherlands, euthanasia advocacy groups and self-euthanasia support groups such as the ‘De Einder Foundation’ are active in handing out advice to people who still want to end their life outside of the mainstream legal euthanasia trajectory. The foundation actively advises its clients how to get “a humane death under your own control”.

And Dutch psychiatrist Boudewijn Chabot penned two books called “Guide to Dignified Dying” and “Taking Control of your Death by Stopping Eating and Drinking” which discusses in detail “how to make stopping eating and drinking a humane exit”.

The books are essential reading for advocates of “self-euthanasia” and people who wish to die. De Einder recommends taking certain medicine combinations and inhaling helium or nitrogen, but it also talks about starving yourself to death for self-euthanasia, a practice which it describes as a “grey area” under Dutch law.

As preparations for self-euthanasia by starvation, the foundation recommends people prepare by talking to doctors and making sure they have a written medical advance directive in which they note down their wishes, including “banning life-extending treatment, fluid administration and hospitalisation”.

It also recommends those with a wish to starve themselves get a special “mattress to lay down comfortably and to prevent bedsores”, exactly as Noa did in having a special hospital bed in her living room. Further steps detailed by the organisation are to consult with a doctor who can “advise daily on soothing medication for stressful symptoms such as anxiety, restlessness and breathing problems”.

It also advises on how to avoid issues for those left behind and significantly points out that of the three alternatives to end life, only one, the one used by Noa, could be used without potential problems for her family. It reads: “Self-euthanasia by refusing to eat or drink is classed as a natural death. Self-euthanasia when using medicines or helium are considered an unnatural death.”

The police confirmation they were not investigating any suspicious deaths was further indication that the method chosen by Noa was the same as the one recommended in the book. If it had been the use of helium or the medicine, a forensic pathologist would need to have been involved. They would need to inform the police and the public prosecutor’s office and the relatives of the deceased would have been questioned as to whether they were actively involved in the “self-euthanasia” process. If they had been actively involved, this would have been illegal.

Noa Pothoven showing the autobiography she wrote.

The death of Noa caused a worldwide media sensation, with even Pope Francis commenting, saying that “euthanasia and assisted suicide are a defeat for all”. Similar voices were echoed in Dutch politics, where active debates have been going on in recent years in which proponents vouched to extend the right to euthanasia while opponents argued for more restrictions.

One of the debated proposals would see all over-75s given the right to assisted suicide when they feel they have had “a fulfilled life” and nothing much more to live for, even in the case when they are in healthy shape. According to the political parties led by the left-liberal D66 Party, a few conditions would have to be met first. There has to be a “sustainable, well-considered and intrinsic” wish to die. A specially trained “life-ending consultant” would give their verdict about the person’s wish to die, which has to be seconded by another consultant or checking committee.

The life-ending consultant would have at least two interviews with the OAP, with at least two months between, to make sure the person knows what they are deciding and that they are not being pressured by their environment. The life-ending consultant could be a doctor, a nurse, a psychologist or a psychotherapist. Pro-life and conservative parties in parliament are actively fighting against what they consider to be a “culture of death”.

Spokesman Cornel van Beek of the Christian-conservative Reformed Political Party (SGP) called upon the government to do more to prevent suicide and self-euthanasia. Van Beek said his party has actively fought in the Dutch Parliament against organisations such as De Einder handing out advice to people on how to end their lives. He said that his party also stood up against a Dutch end-of-life advocacy group group called ‘Laatste Wil’ (“Last Will”) when it started distributing a deadly substance to its members in 2017 so they could end their lives on their own terms if they wished to do so.

While the substance was initially meant for the elderly who have lived a “fulfilled life” with nothing more to live for, the organisation even opened its doors for younger people to acquire the substance in the form of a powder which people need to mix with water and drink in order to die.

Van Beek said: “People get a wrong signal from this. Instead of people being aided psychologically or searching help in different ways, they can now just choose this option for a way out.” Van Beek said that many people have psychological problems and that especially among youngsters this can cause problems in their life, but added that it does not mean “that in the future they cannot have a positive life outlook”. He added that there are many examples of people having successfully overcome mental problems.

He added: “We find it very worrisome that some organisations are sending signals to society where they detail how you can end your life. Death is never a medical solution. We should always search for other ways out.”

Michael Leidig is an editor and publisher. Republished here with the permission of VT.