What The Parable Of The Ten Lepers Teaches About Gratitude

Humans are not good at thankfulness.

Every parent has those days. Mine was Saturday.

I took two of my kids to the budget theater to see Incredibles 2. We ate buttered popcorn, drank Cherry Coke, and chewed candy. It was a great time until my seven-year-old daughter wanted to play “the claw game.”

I’ve told her before the game is a ripoff. But she had her own money, and we believe in giving our children choices (within reason). She played and lost. Then she reached in her little black purse and grabbed a second dollar. She lost again. Tears ensued, then anger. It ended with me dragging her out of the theater as her little brother looked on wide-eyed. Our happy day was ruined.

Just like that, I had failed as a parent.

Little brat, I thought. How ungrateful.

I was upset with her and the fact that our nice day had soured. But there was also something more.

Just like that, I had failed as a parent. It starts with claw game tantrums. Then it’s sex and drugs, everyone knows... Okay, not quite. But the truth is my wife and I try very hard to teach our children to be thankful for all they have. That message was not getting through to my daughter in that moment.

Gratitude Does Not Come Easy for Humans

As it happened, the next day I received a powerful sermon on gratitude at church. The pastor, Joel Johnson, a wonderful speaker and leader of Westwood Community Church, said if there was a single quality he could increase in our world today, it would be gratitude. Listening closely, I nodded through his entire sermon.

There is, of course, abundant research showing the utility of gratitude. It makes us happier. It makes us more successful. It makes us better leaders.

In his 2008 book, Thanks! How Practicing Gratitude Can Make You Happier, Robert A. Emmons, who spent years studying gratitude, wrote that

grateful people experience higher levels of positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, love, happiness and optimism, and that the practice of gratitude as a discipline protects a person from the destructive impulses of envy, resentment, greed and bitterness.

One would think this would make gratitude easy for us. Who doesn’t want to be happier and more successful? Alas, gratitude, for all its merit, is not something easily embraced, evidence suggests.

The most obvious example, of course, is the presence of the “victimhood culture,” which has turned grievance into a fad. There is indeed something odd and troubling about an ideology that stokes the embers of our resentment, particularly in a time and place enjoying unprecedented wealth and opportunity.

But look closer. How often do you feel grateful? More importantly, how often do you express and show your gratitude to others? If we’re honest, the answer is probably the same for most of us.

Not enough—not even close.

Why does gratitude come so hard to us? Why do feelings of entitlement and envy invade our thoughts?

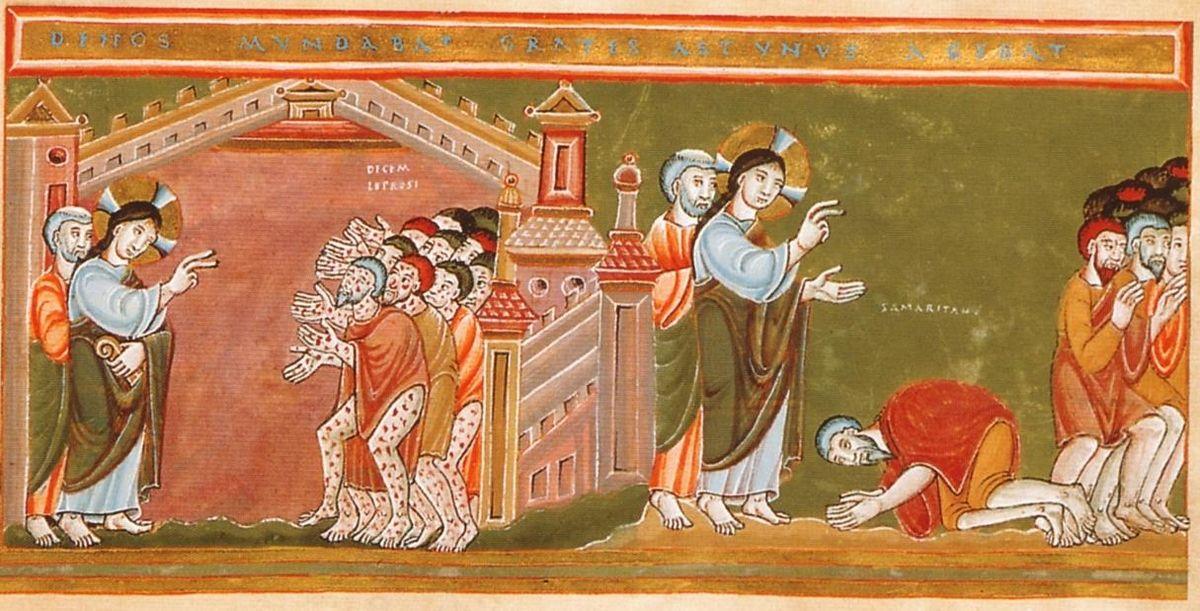

Jesus and the Ten Lepers

I’ve read or been told the story of Jesus healing the ten lepers probably ten times in my life. Yet somehow the message of gratitude—or, rather, human ingratitude—escaped me until Pastor Joel hit me over the head with it Sunday.

The story appears in Luke 17. Jesus of Nazareth is traveling along the border of Samaria and Galilee when the lepers call out to him.

“Jesus, Master, have pity on us!”

“Go, show yourselves to the priests,” Jesus responds.

The lepers go to the priests and are cleansed, Luke tells us. But the story doesn’t end there. A single leper, a Samaritan, returns and throws himself at the feet of Jesus. Of the ten lepers healed, a single one returns.

The most powerful takeaway for me is the idea that humans struggle mightily with gratitude.

“Were not all ten cleansed? Where are the other nine?” Jesus asks. “Has no one returned to give praise to God except this foreigner?”

Luke does not tell us how the Samaritan replies. But Jesus tells him something before sending the man on his way. “Rise and go; your faith has made you well.”

There are several takeaways from the story. The idea that gratitude is part of being “well” is certainly present. This comports with the findings cited above.

But the most powerful takeaway for me is the idea that humans struggle mightily with gratitude. This apparently includes people cured of infectious skin diseases, as well as those of us who live amid unprecedented peace and prosperity.

Getting Serious about Being Grateful

The day after my daughter’s meltdown at the theater, she and her little brother were each given a silver dollar. They could do what they wanted with it, they were told, but were encouraged to give the coins to the boys in red ringing bells outside the church.

My daughter put her coin in the Salvation Army bucket and instructed her somewhat more reluctant little brother to do the same. In the car, as we sped home, she explained to him why they did the right thing.

Gratitude is not earned so cheaply. It is hard. Moreover, gratitude requires not just feeling thankful but acting on it. Living it.

“There are kids who don’t have food in their tummies, like none,” she explained. “And they don’t have presents or families like we do.”

I have no illusions, for my children or myself, about the happy ending to my story. Gratitude is not earned so cheaply. It is hard. There is something in the human constitution that draws us toward its adversaries, envy and entitlement. Moreover, gratitude requires not just feeling thankful but acting on it. Living it.

Thanksgiving is a wonderful time. The football games, feasting, and family fun are a big part of it. But these things cannot be allowed to eclipse its true purpose. For perhaps the first time, I truly believe in the power of gratitude, which is why I’ll close with a message.

As a people, Americans need to get this right. Philosophy matters. If entitlement, envy, and resentment overcome our better angels of gratitude, generosity, and goodwill, the price will be high. We won’t just be miserable—we’ll one day realize we let evil slip in through the front door.

Jon Miltimore is the editor at large of FEE.org