32,000 Medieval Manuscripts Made Searchable in Months by New Digital Humanities Project

Researchers at France’s Inria have used artificial intelligence to transcribe 32,763 digitised medieval manuscripts in just four months, creating the CoMMA corpus, one of the largest searchable collections of premodern texts ever assembled.

Medievalists can now consult automated transcriptions of 32,763 digitized medieval manuscripts, produced in just four months through CoMMA (Corpus of Multilingual Medieval Archives), a large-scale project that makes manuscript texts searchable and analyzable on an unprecedented scale.

The work was carried out by computational humanities researchers at Inria, France’s national institute for digital science and technology, in collaboration with partners in France and Switzerland. The project builds on earlier efforts to overcome the difficulties of automating medieval handwriting, which is marked by non-standard spelling, evolving languages, abbreviations, and highly variable scripts.

Thibault Clérice of Inria explained that, until now, individual specialists have gone their own way when transcribing these manucripts from the Middle Ages. But automated manuscript transcription requires not only machine learning, but also standards.

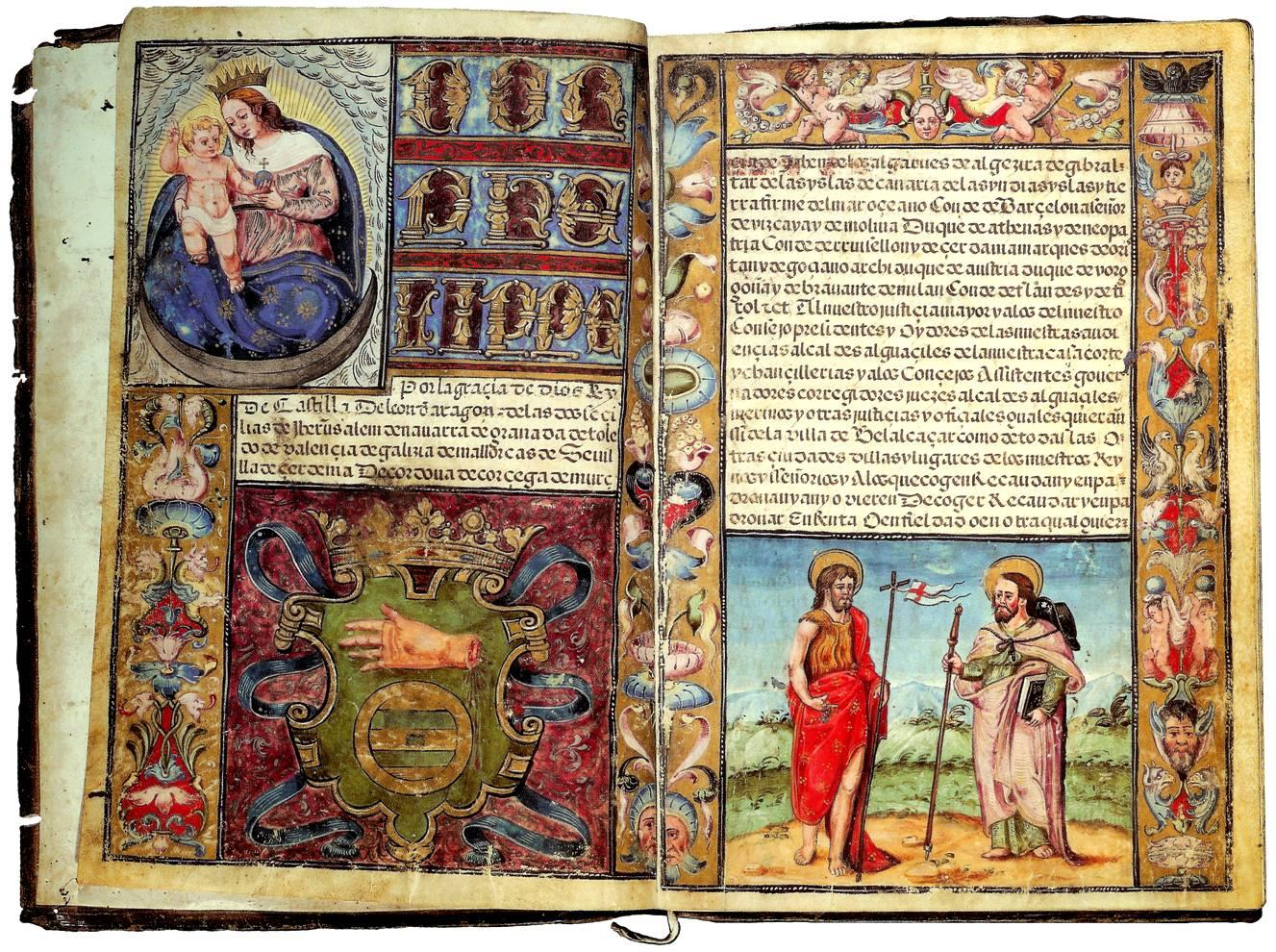

Those standards were developed through CATMuS, an initiative launched in 2022 that aligned about 200,000 lines from 300 medieval manuscripts, dating from the 8th to the 16th centuries and written in multiple languages, chiefly Old French and Latin. This uniform corpus allowed researchers to train a handwriting text recognition model using tools such as eScriptorium and Kraken, with an emphasis on efficiency and fidelity to what appears on the page rather than speculative linguistic interpretation.

CoMMA, launched in 2024, applied this trained model at scale. Using digitised manuscript catalogues aggregated by Biblissima+, the team expanded from hundreds to 32,763 manuscripts, transcribed in four months. The system combines page-layout analysis with automated transcription of the text itself.

Manual checks of sample lines in 670 manuscripts showed an error rate of 9.7%, with most errors arising from very early manuscripts or difficult cursive hands. Further improvements are possible, though Clérice notes that gains must be balanced against processing time. He also stresses the project’s collaborative nature, observing that “Digital expertise alone would not have allowed us to understand as well the manuscripts we were processing.”

Beyond its technical achievement, CoMMA offers new possibilities for research. The searchable corpus enables large-scale study of medieval writing practices, abbreviations, layout, and linguistic variation. The scale is dramatic: Old French pseudo-words increase from 11 million in previous corpora to 516 million in CoMMA, while Latin grows from 226 million to 2.7 billion.

Elena Pierazzo of the University of Tours said that the resulting digitized documents will alter how readers process such textual data, while it offers new ways for studying how language evolved over time.

The team plans to expand CoMMA beyond Old French and Latin to other languages, including Spanish and Italian. For medievalists, the project suggests that future discoveries may come less from unearthing new manuscripts than from finally being able to search and compare existing ones at scale.