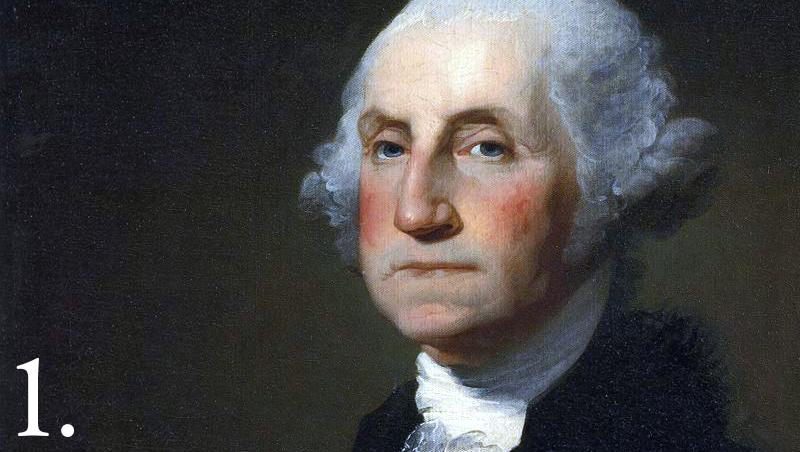

George Washington: A Champion For All Americans, And Catholics

When other Americans deemed Catholicism subversive, Washington saw Catholics as friends and allies.

On Presidents’ Day dawns, reminding us of the leaders who shaped our nation, it’s fitting to revisit the unparalleled legacy of George Washington, the holiday’s original honoree. Our first president was a monumental leader; he led the Continental Army through the Revolutionary War, unified the discordant states during the framing of the Constitution, and steadied a young nation. And unlike many in the Founding generation, Washington defied widespread anti-Catholic prejudice, establishing the religious liberty central to America today.

Anti-Catholic bias ran deep in early America. Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. called it “the deepest bias in the history of the American people.” Many of the first colonists were Puritans and Congregationalists; they came to America to escape persecution by the Church of England, whose doctrines they associated with Catholicism.

As a result, many early Americans linked their faith with liberty and Catholicism with tyranny. They believed Catholics could never be fully American because allegiance to the Pope and obedience to Church hierarchy seemed incompatible with republican self-government. Anti-Catholic rhetoric later framed the American War of Independence as resistance not only to Parliament but also to Rome. Colonial laws reflected this hostility.

Yet Washington championed religious liberty for Catholics, viewing it as the government’s “very first imperative,” according to scholar Michael Novak. In a 1785 letter to George Mason, Washington wrote that “no man’s sentiments are more opposed to any kind of restraint upon religious principles than mine are.” He insisted that good citizens be “protected in worshipping the Deity according to the dictates of their own conscience.”

To Bishop John Carroll, the first U.S. Catholic bishop, Washington wrote that growing liberalism would ensure all worthy citizens are “equally entitled to the protection of civil Government.” He praised Catholic patriotism and Catholic France’s vital aid during the Revolutionary War, affirming their full and equal place in the American experiment.

Washington put these convictions into action. During the War’s 1775–1776 Quebec Campaign, he banned the anti-Catholic “Pope’s Day” (called Guy Fawkes Day in Britain) effigy burnings on November 5, calling them “ridiculous and childish” and “monstrous” whilst seeking alliances with Catholic France and Canada. He warned his forces against any disrespect or contempt toward the Catholic residents of Quebec.

Washington was also impressed by Catholics for their brave contributions to the cause of independence. Among them was Commodore John Barry (first U.S. Navy officer under Washington), aide Captain John Fitzgerald, French ally Marquis de Lafayette (highly esteemed by Washington), and Charles Carroll of Carrollton—the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence—who financed the war, served on the Board of War supporting Washington, and became his friend.

Personally, Washington showed warmth towards Catholicism. He occasionally attended Catholic Mass, led a delegation from the Constitutional Convention to a nearby Mass at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, visited America’s first Catholic college, financially supported the construction of Catholic churches, and displayed religious paintings of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist at Mount Vernon. Reports from his aides and servants note he made the Sign of the Cross before meals and prayer, a distinctly Catholic gesture. Biographer Ron Chernow observed that Washington “believed in the need for good works as well as faith,” diverging from the typical Protestant emphasis on salvation through faith alone.

In a society that deemed Catholicism subversive, Washington treated Catholics as equals and friends.

Catholics returned the regard. Bishop Carroll praised Washington’s religious respect in 1790 and eulogized him twice after his death in 1799, calling him America’s truest friend and Providence’s instrument. Pope Leo XIII, in 1895’s Longinqua, cited the “well-known friendship” between Washington and Carroll as the model of harmony between the U.S. and the Church. Pope Pius XII in 1939’s Sertum Laetitiae called Washington and Carroll “close friend[s],” an example of the reverence for Christ that grounds America’s morality, prosperity, and progress.

America has always had competing impulses toward the Catholic Church: one generous and confident, another fearful and tribal. Washington is worth celebrating because he chose the better impulse. He was a true friend to the Church when Catholics needed it, paving the way for their emancipation from vicious laws and biases against them.