The US and its Wrong-Headed Approach Towards Corruption and Growth

It's a case of the kettle calling the pot 'black'.

The US government has prioritized the fight against corruption in the developing world, as reflected in the official policy of the US State Department. This policy carries over into USAID policy, and nowhere is this policy implemented with greater force than in Central America, Guatemala especially.

This corruption crusade has revealed new heights of hypocrisy and undermined diplomatic relations with key allies. Amid the tension, China is seizing the opportunity and gaining ground in Latin America, both commercially and militarily.

In a nutshell, the theory upon which this policy is predicated is that by controlling corruption and fortifying institutions in countries such as Guatemala, economic growth will follow. With more economic opportunities, illegal immigration flows into the United States will diminish.

Given many accusations of the politicization and corruption of once revered US institutions (the State Department, the FBI, the Justice Department, and the CIA) and leading US politicians (Pelosi and Biden), it is no wonder that this otherwise persuasive argument often falls on deaf ears abroad. Foreign political, business, academic, and civil-society leaders follow current events in the United States closely. Many are aware that the premise that the United States is in a higher moral position to dictate to other countries how they should run their affairs is shaky, to say the least.

The United States is the developed country with the worst grades on control of corruption, according to the latest World Bank data. On this variable, the United States ranks 34th in the world, not even close to being in the top 25. The United States scores worse than Andorra, the Bahamas, Bhutan, Brunei, and even the United Arab Emirates.

The poor example and credibility that the United States presents to the world notwithstanding, the US policy is correct in associating greater control of corruption with higher levels of economic development and quality of life. Developed countries like the United States score better than the world average on the fight against corruption, economic performance, and any other indicator of well-being. The data of the different indicators are too numerous to mention here, but correlations are easy to verify.

Nevertheless, the clear association between control of corruption and well-being says nothing about how countries arrived at better grades for the fight against corruption and development. Lant Pritchett, the Oxford University development economist, argues that the general rule is that countries grow first and then control corruption. According to Pritchett, it is not the case that developing countries first have to get to a “rules world” to achieve substantial economic growth. The key is, once having started an episode of growth, to generate a positive feedback loop where growth begets institutional improvement, which in turn sustains economic growth.

Pritchett’s argument flips the US anticorruption strategy on its head.

There are many reasons to question the US corruption-growth narrative. First, there is the political argument. The United States pressures key allies in Central America, like Guatemala—at times aggressively—and tries to impose a quick fix on an enduring corruption problem. This has caused great political turmoil in Guatemala. China, which has made enormous inroads into Latin America, makes no such demands on the countries it trades with and invests in.

When pressuring its key allies in Central America, the US narrative is that foreign investment will not come where there is corruption or lack of democracy. That narrative is demonstrably false. For example, the United States itself is a leading investor in China. It has increased its investment in that dictatorial country eleven-fold since 2000. After the United States, China is the top destination for foreign direct investment in the world, so it is not only US companies that choose to invest where there is no democracy and plenty of corruption.

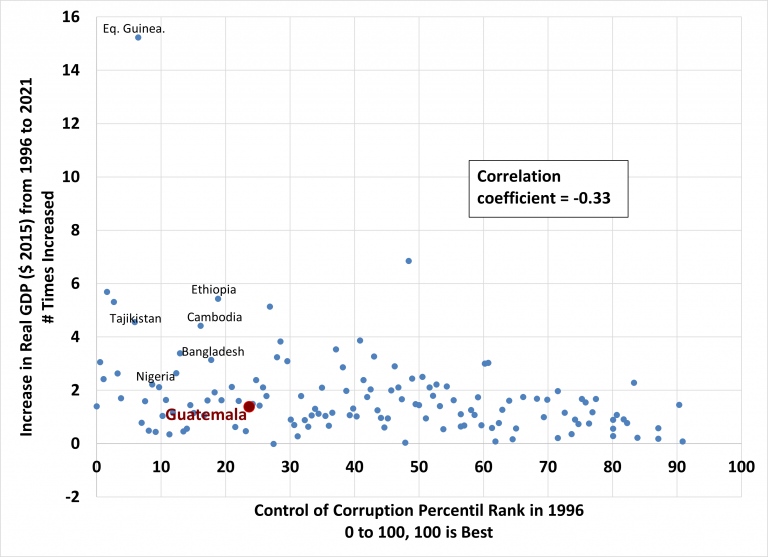

Second, there is the economic argument. Less corruption has not proved necessary for greater economic performance. The historical data on corruption is of recent creation, unfortunately, but since 1996 the World Bank has kept records of countries in matters of governance, with its worldwide governance indicators. If one takes the 136 developing or transitioning countries with percentile rankings (0 to 100, 100 being best) in 1996 and compares each to its corresponding increase in gross domestic product (in constant 2015 dollars) from 1996 to 2021, the correlation is negative (-0.33)—although only moderately so.

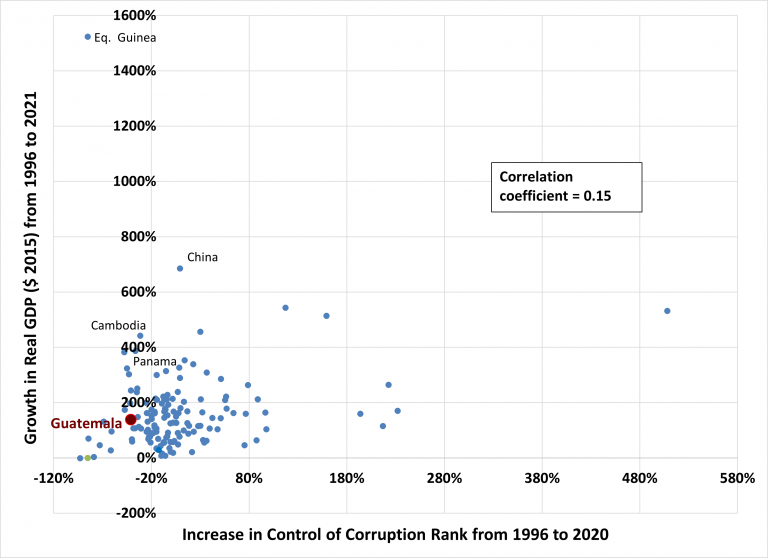

Another way to analyze the relationship between the control of corruption and economic growth is to measure the change in percentile rank for control of corruption against the percentage change in real GDP. This measure reflects for 137 developing or transitioning countries a positive correlation, but a paltry and insignificant one (0.15). Various countries faltered in their percentile rankings for control of corruption, but they still managed to increase their GDP substantially. Cambodia and Panama stand out. Some cases point to the contrary, like Myanmar, Iraq, and Georgia.

The political and economic dimensions of the US argument to prioritize corruption above all else, in an attempt to provoke positive changes, are backfiring. China is reportedly seeking a naval presence in Nicaragua, which would be a permanent game-changer for US security interests. As the United States attacks its most steadfast allies, like Guatemala, it is missing the greater picture: China is landing on US shores.

The United States would do well to get off its high horse and work with proven allies in its own interests.

Nicholas Virzi is a professor of international relations at Francisco Marroquín University in Guatemala City.

This article first appeared at ImpunityObserver.com