Before Pope Francis, A Compatriot Had Already Imagined An Argentine Papacy

Juan XXIII (XIV) by Castellani has been compared to another forgotten novel, written by Frederick Rolfe, who was also controversial.

There have been perhaps countless novels set against the backdrop of the Vatican, often driven by obvious anti-Catholic animosity, in which popes, usually entirely fictional, are involved in incredible adventures or fall victim to sinister plots.

In "Juan XXIII (XXIV)", a very Catholic novel, prophetic in many ways and seasoned with Cervantes-style humor, the Argentine Leonardo Castellani (1899-1981), dared to imagine a compatriot sitting at the See of Saint Peter, half a century before Pope Francis.

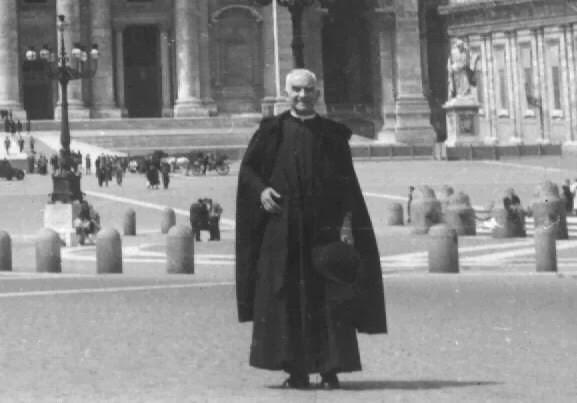

Castellani was a devout Catholic priest, theologian, psychologist, and one-time Jesuit, who was a writer gifted with unique expressiveness, profound erudition, and a quick mind. He had the sensitivity of a great poet, which allowed him to see more deeply, and the clairvoyance of a great prophet, which allowed him to see further than most. In addition to these rare qualities, he also had the precious and divine gift of contemplating things as a whole, the ability to know both the natural and the supernatural at the same time, with the gaze of an eagle always fixed on the eschatological horizon, from which Christian hope draws its strength.

Castellani cultivated literary genres ranging from poetry and novels, stories and essays, literary criticism, political and social analysis, as well as biblical exegesis. He imbued all these genres with his own style, which was polemical and apologetic. We see in them the suffering man that he undoubtedly was, but also the man who, in the midst of his trials, had bound himself in obedience to Jesus Christ to preserve the integrity of his freedom. After being expelled from the Society of Jesus and suspended a divinis in 1949, Leonardo Castellani was fully reinstated in his priestly ministry in 1966. The charges against him were never explained, and a canonical trial was denied, as was an appeal. The episode was traumatic for him and left a deep mark on his life and work, in which he is capable of wielding both the whip of a Leon Bloy or a Hilaire Belloc, and the magic wand of a G.K. Chesterton.

The novel "Juan XXIII (XXIV)", a kind of purification of the heart or coded autobiography, was published in 1964 in the midst of the Second Vatican Council, which had been called by the very real Pope John XXIII. The novel draws on Castellani's erudition and wit. It is strongly influenced by another very famous novel about the papacy, "Hadrian VII" by Frederick William Rolfe (1860-1913), better known by his pen name, Baron Corvo. As in this novel, the protagonist of Castellani's book, Pio Ducadelia, the son of Italians, is the author himself: a “Hieronymite” monk—we soon discover that this Hieronymite order is a representation of the Society of Jesus—who had been forbidden to celebrate Mass, but was then suddenly reinstated and sent to Rome as advisor to the Archbishop of Buenos Aires.

In the novel, the Vatican Council had just begun and, halfway through the proceedings, the sessions were transferred to the Lateran Palace due to political complications that soon escalated into a violent “Russia-Europe conflict.” During the conflict, the Soviets dropped bombs on the major capitals of Europe, before losing to an alliance of countries that restored the monarchies in Italy and France. At the council, discussions continued against a backdrop of uncertainty and unrest. Pio Ducadelia participates as a papal theologian after surprising Pope John XXII (Angelo Roncalli) with his proposals for reform aimed primarily at combating—and we quote—“impersonal bureaucracy in the management of ecclesiastical matters.”

To achieve this reduction in bureaucracy, Ducadelia proposes, for example, “decentralizing ecclesiastical government by appointing patriarchs, as was the case in the 5th century,” and establishing a “Papal Council” made up of twelve experts, “each affiliated with a branch of government.” Ducadelia also proposes a “revision and adaptation of ecclesiastical celibacy to make it more rigorous and decent”; he also suggests to the pope, in order to avoid any financial scandal, that “neither bishops nor religious orders should be allowed to possess credit documents of any kind,” and that “all ecclesiastical property” should instead be “invested in real estate, the income from which would be entrusted to the Carthusians and Trappists.”

But the council was dissolved in the face of the Soviet threat, and the pope was forced into exile, where he died after recommending—before the diaspora of the College of Cardinals—that his successor be elected by only three delegates. Ducadelia was captured and taken to Russia, where he was subjected to horrific torture. Upon his return to Rome, he was astonished to discover that he had been elected pope. To show his filial veneration, he decided to take the name of his predecessor, John, as well as his number, justifying his decision as follows: "There was no John XX. There was a John XV, who died barely a month after being elected and without having been canonically crowned. There was a John XXIII during the Avignon schism, who was not a legitimate pope. So our venerable predecessor, as required by the historical rigor of the numbers, is named John XXII. And so all the Johns in retro, removing one digit from each number... up to XV."

From the outset, the new John XXIII (or XXIV) declared that the main task of his pontificate would be to fight for the “inner purity” of the Church and against what he considered to be “clericalism,” which he described as follows: "These are all those decrepit magnates who do not want change in the Church because it suits them fine as it is; and it suits them fine because they are deprived of touch and smell (and sight, of course) and do not realize that they are alone, that the world is silently moving away from the Church... Alone and complacent in their childish honors and comforts... of women. ‘Ecclesiasticism’ is the worst heresy in the Church today."

To wage the “battle for inner purity,” Ducadelia reduces Vatican bureaucracy by two-thirds, believing it to be “a machine and therefore untouchable.” “This machine, which already has a brain at the top, must be equipped with a heart at the center and tactile papillae at the extremities,” he added, “where it comes into contact with living human beings; for the priest is, or must be, human.” In his search for priests endowed with human warmth, Ducadelia will not hesitate to punish fallutos (in Argentine Spanish, hypocrites or fakes) and reduce the salaries of the curia, arousing great discontent and antipathy around him.