Russia’s Fight for Ukraine’s Natural Resources

Ukraine’s right to democracy, freedom, and self-determination is threatened by conflicts over energy and food economics. In an interdependent world, President Vladimir Putin, a former KGB agent, has determined that blatant warfare is more desirable than peaceful trade negotiations. He is intent on Russia controlling Ukraine’s mineral resources and agricultural land. The Russian people are protesting this war, recognizing the rights of their Ukrainian brothers over Putin’s financial greed.

This is not the first time Russia has sought to leverage Ukraine’s resources for its own purposes. Josef Stalin, during the wider Soviet famine of the early 1930s, systematically starved the Ukrainian population for the ostensible benefit of Soviet Russian workers—a near genocide now known as the Holodomor.

What does Russia gain from an all-out assault on Ukraine? The war traces its roots to the 2021 suspension of the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline built by Gazprom, the Russian natural gas company, because of its failure to comply with the EU’s anti-competitive laws. The new pipeline would have doubled Germany’s energy resources from Russia through the Baltic Sea in exchange for exported German technology—bypassing Ukraine and the need to pay transit fees. Once operational, however, Germany would have been dependent on Russia for up to 70 percent of the country’s natural gas needs; the European Union (EU) currently receives nearly 40 percent of its gas from Russia.

If completed, Nord Stream 2, together with the Nord Stream 1 pipeline (2011) from Russia to Germany and the southern pipeline in the Black Sea from Russia to Turkey (TurkStream, 2020) would divert natural gas away from transit pipelines in the Ukraine to the EU. Ukraine’s ten–year gas contract with Gazprom expired in 2019. The US imposed sanctions in 2019 to initially stall the construction of Nord Stream 2, forcing Gazprom to extend Ukraine’s agreement by five years. Although sanctions were waived by the US in 2021, Germany stalled project certification in late 2021 to review compliance concerns with EU laws. Gazprom retaliated by reducing Ukrainian annual gas transit flows to the EU. As a result, natural gas prices in the EU have risen by 125 percent over the past six months and will rise further in the near future.

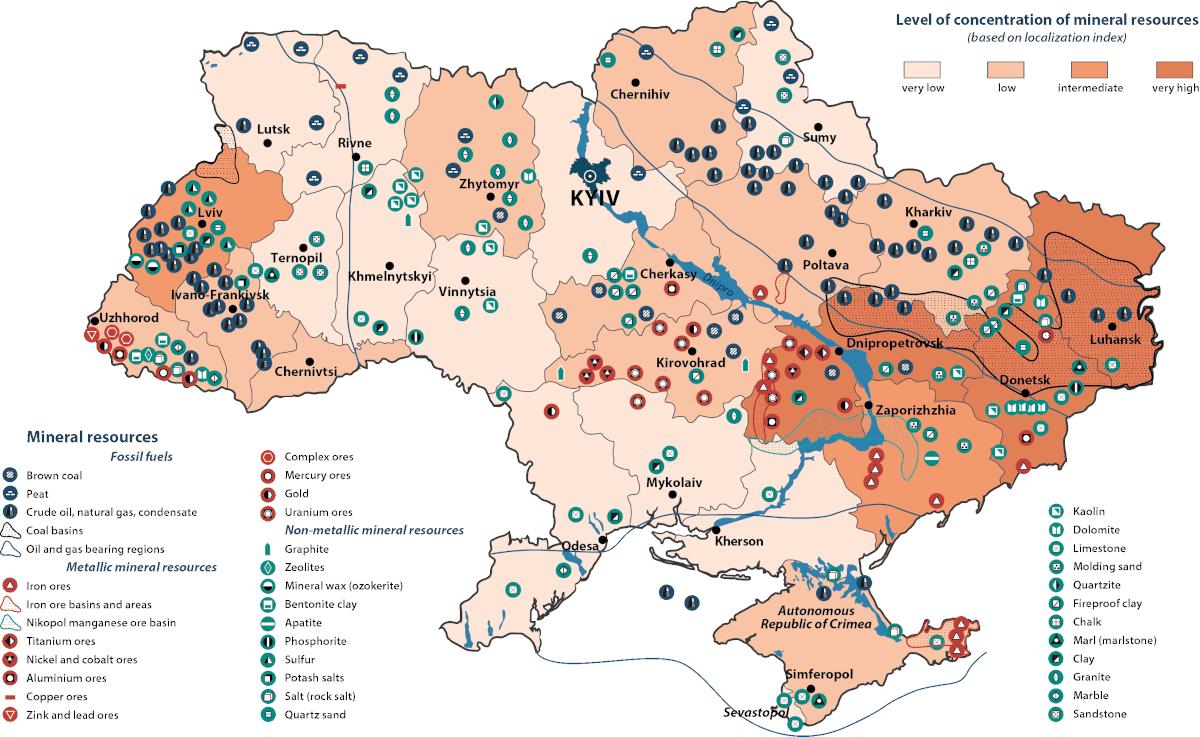

There are significant energy resource implications in the invasion of the eastern Russian-separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk as well as in Ukraine’s surrounding border regions. Donetsk and Luhansk are home to some of the largest coal and natural gas deposits. Luhansk is a key entry point for the Soyuz pipeline carrying Russian gas through Ukraine to the Balkan and southeastern European nations. Were these provinces to split off into independent states, Ukraine would lose future revenues while Russia gained access to significant mineral resources.

If Russian forces succeed in holding the city of Kharkiv, northwest of Luhansk province, troops could move into Ukraine’s interior. Not only are significant natural gas and coal deposits in production along this corridor, but enormous amounts of potential deposits still exist throughout the Donets coal region and the Dneiper-Donets oil and gas basin. As Russia increases gas prices, the EU could shift to using lower-cost and easily available coal. But if Russia controls the coal basin, Putin could threaten the EU with pricing pressure on this resource.

EU countries are currently maintaining-lower-than normal natural gas reserves, at an average 31 percent below capacity for this time of year, roughly half that of 2020. To increase supplies, the EU needs to diversify resources by increasing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the US and Qatar, while maximizing pipeline flows from Algeria, Azerbaijan, and Norway. Natural gas must be cooled to a minus 260 degrees to be condensed into liquid form for storage, then shipped to specifically designed seaport centers. This dynamic is already raising energy prices on the world markets and the US stands to gain from LNG exports.

Along with coal, the EU might shift to using alternative energy and nuclear power. Ukraine has one of the largest deposits of uranium in the world, which is at risk for takeover by Russia. Coal use will challenge the continent’s timeline for meeting future climate targets. Alternative energy resources will not meet all the EU’s needs. Natural gas remains the most cost-effective short term transition option and is not likely to disappear in the near future.

Ukraine is the breadbasket of Europe. Seventy percent of the country’s land is utilized for growing wheat, corn, barley, and sunflower seeds, with its largest agricultural exports shipped to Egypt and Turkey. The entire region east of the Dneiper River is used for farming. The river traverses central Ukraine, beginning north of Kyiv and running southeast then southwest toward the Black Sea port cities of Kherson and Odessa. Should Russia gain access to this land, grain export prices will rise, as they already have done, and Russia can threaten political extortion against Turkey and Egypt. More important, if the Russians take over Kyiv, they will almost certainly install a puppet government, as in Belarus, making incursions beyond Ukraine possible.

Russian battleships and forces are now targeting the southern seaport cities of Odessa and Kherson, as well as additional agricultural land to the north of the Crimean Peninsula. When Russia annexed the Peninsula in 2014, the country gained control of maritime corridors for completion of the Black Sea pipeline system to Turkey and the EU. Russia also gained access to promising oil and natural gas deposits in the Black Sea off the coast of the peninsula.

The EU’s aggressive economic sanctions against Russia are reinforcing new Russian alliances with China as Russia seeks energy markets outside the EU. Gazprom recently signed a 30–year natural gas agreement to double current exports to China via Russia’s newest “Power of Siberia” pipeline. These two countries have also signed an agreement for Russia to provide 100 million tons of coal in a long-term agreement.

The EU and NATO were initially weak in their support of Ukrainian defenses. European nations feared Russian retaliation as their economies depend on trade with Russia. Not being part of NATO, Ukraine was forced to fight alone. If the US military becomes directly involved, this would be viewed as an act of war against Russia. Fortunately, as the conflict escalated, the US and the EU acted quickly, leveraging economic sanctions against Russian banks, oligarchs, and technology while sending more defense equipment to the region.

Showing weakness or silence when one country is invaded for its economic resources is a threat to the values of freedom and self-determination for every country in Europe. An autocrat like Putin understands military strength and NATO’s unwillingness to commit defense resources demonstrates weakness. Only recently has NATO been willing to send significant military equipment and aircraft to assist the Ukrainian people. As Putin places Russia’s nuclear deterrent forces on high alert, the continent—and the world—are on notice that another World War is again possible.

Cultural ethicist Faye Lincoln is the author of Values That Shape the World: Ancient Precepts, Modern Concepts (Dialog Press, 2021). She analyzes the values-based implications of US and Middle Eastern policies based on history, religion, economics, and public policy.