From Sanskrit to English: Tracing the Violent Spread of Proto-Indo-European

Linguistic clues, ancient migrations, and DNA evidence reveal how a vanished Eurasian tongue reshaped the languages of Europe and Asia. From Sir William Jones’ 18th-century insight to modern genetics, scholars uncover the migrations and conquests behind the Indo-European family.

In 1786, the British judge Sir William Jones in Calcutta made a stunning observation. Sanskrit, the ancient language of India, showed a striking similarity not only to Greek and Latin in a few words, but in their entire grammar and structure. He suspected that all three languages must have a common origin, “perhaps no longer existing”.

He was right. That source is what we now call Proto-Indo-European: a language spoken more than six thousand years ago by a single speech community somewhere in Eurasia. We possess no records, no written texts of it. And yet linguists have reconstructed thousands of its words.

How? By comparing the daughter languages and finding patterns that are too systematic to be coincidence.

The similarities are no coincidence. On closer inspection, one recognises that the differences follow rules. Where Latin has a “p”, English has an “f”. Where Latin has a “d”, English has a “t”. Always. Systematically.

In 1822, Jacob Grimm (yes, the fairy-tale collector) formalised these patterns in what is now known as Grimm’s Law. It describes how an entire series of consonants changed as Proto-Indo-European developed into the Germanic languages.

If Proto-Indo-European was a real language spoken by real people, when did these people live? Linguists found the answer hidden in the reconstructed vocabulary.

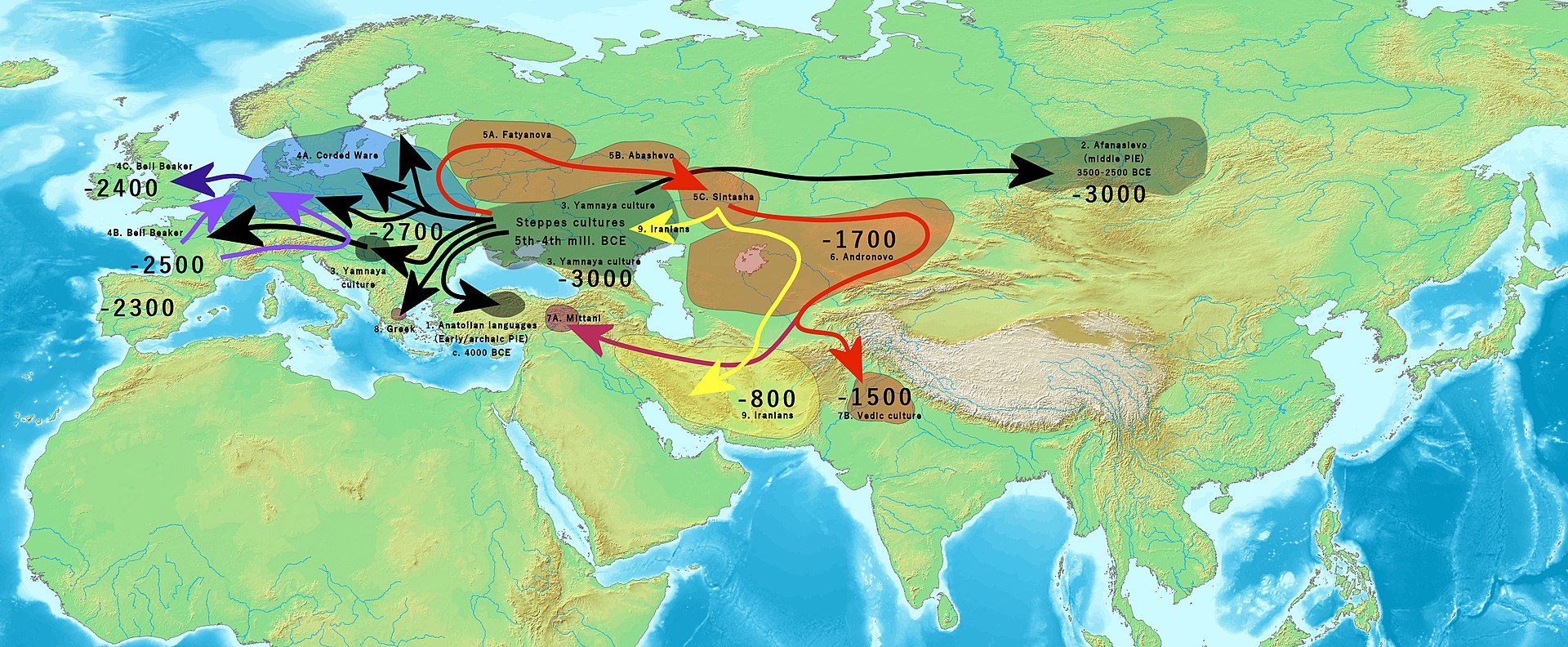

The Pontic-Caspian steppe, the vast grasslands stretching from present-day Ukraine to Kazakhstan, is considered by researchers to be the homeland of Proto-Indo-European. From here, their descendants spread the language across half the world over two thousand years.

Knowing where the Proto-Indo-Europeans lived is only half the truth. The deeper puzzle is how a single language spoken on the steppe could come to dominate half of Eurasia. The answer lies in horses, wagons, milk, bronze and an extraordinary series of migrations that spanned millennia.

For decades scholars debated how a single language could spread over such a vast area. One group argued for elite dominance: a small ruling class (warriors, priests, chieftains) imposed their language on conquered peoples, much as Norman French displaced English after 1066. The native population survived, but their children grew up speaking the language of the newcomers.

The alternative was mass migration: entire population groups moved into new territories and replaced or assimilated the previous inhabitants. For a long time, elite dominance was the prevailing theory. Then came ancient DNA.

From around 2015 onwards, palaeogenomic studies revealed a dramatic genetic turnover in Europe around 3000 BC. In many regions, 70–100 % of male lineages were replaced within a few centuries. The Yamnaya and their descendants did not merely rule — they also migrated in enormous numbers. The debate is not yet finally settled, and both mechanisms probably operated at different times and places, yet the DNA evidence has decisively shifted the balance of evidence in Europe towards mass migration as the main driver.

Modern DNA researchers attempt to obscure these facts and present migration as a colourful event in which migration streams simply blend together. In reality, in the past it was regularly more a matter of genocidal territorial conquest, carried out in such a way that the men were exterminated and genetic mixing occurred purely through the appropriation of the women of the defeated.

Dubravko Mandic is a criminal lawyer practising in Germany.