‘Spiritually Naked’ And Really Nude Amazon Missionaries Declared Venerable

On May 22, 2025, Pope Leo XIV advanced the canonization of Spanish Bishop Alejandro Labaka Ugarte and Colombian Sister Inés Arango Velásquez. As their cause progresses, the Vatican News website described them as a man and a woman of peace who “offered their lives in martyrdom for the faith – a violent death in the Ecuadorian rainforest while defending the rights of indigenous peoples.” They have now been declared “Venerable.”

In 2017, Pope Francis issued his motu proprio apostolic letter Maiorem hac Dilectionem, which established the heroic offering of one’s life in service to others as a category distinct from martyrdom in the process of sainthood. Labaka and Arango are now one step closer to beatification, which would require the recognition of a miracle attributed to the intercession of each.

As the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints, under the guidance of Cardinal Marcello Semeraro, continues to examine the lives of Labaka and Arango, it should also consider the Cronica Huaorana, written by Bishop Labaka himself and published by the Apostolic Vicariate of Aguarico, and related works, as part of its research.

Labaka was born in Spain in 1920. In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, he entered the Capuchin Order and took the religious name Brother Manuel. Ordained to the priesthood in 1945, he was sent as a missionary to China. Following the triumph of the Maoist revolution, he and other missionaries were expelled from the country. He was then assigned to Ecuador, where he served as a pastor and apostolic prefect while evangelizing the Huaorani people, who live in a remote northern region of the South American republic.

In 1984, Brother Manuel was consecrated a bishop and thereafter became known by his birth name. It was following the Second Vatican Council that members of religious orders reverted to their baptismal names. That same year, Bishop Labaka established contact with the Tagaeri, a splinter group of the Huaorani. In announcing the canonization process, Vatican News wrote: “It was a time of intense tension. Oil companies moved through the region like predators, clearing forests in search of black gold.” Because of the dense forest canopy, helicopters were used by oil companies and the Ecuadorian military to transport personnel and supplies.

In the manner of the time, Labaka did not seek to evangelize, but rather “to receive from them [the Huaorani] all the ‘seeds of the Word’ hidden in their actual life and in their culture, where the unknown God lives.” Today, the vast majority of those Indians are Protestant.

Sister Inés Arango was born in Colombia on April 6, 1937. In 1955, she entered the novitiate of the Capuchin Tertiary Sisters of the Holy Family and took the name Sister María Nieves de Medellín. She made her first profession in 1956 and later taught at an elementary school in Colombia. In 1977, she became one of the founders of a missionary house in Aguarico, in Ecuador’s Amazonian region, where she served as superior. It was there that Bishop Labaka and Sister Arango became acquainted. Together, they ministered to the Huaorani and lived among them for extended periods. It becomes clear in the Cronica Huaorani that Labaka was at times nude in the presence of Arango when she remained clothed.

According to Vatican News, Bishop Labaka and Sister Arango were aware of the conflict between oil exploration companies and the Tagaeri tribe. The Tagaeri have long resisted contact with outsiders, sometimes attacking and killing them. Because of their isolation, it is difficult to determine their population, but they are estimated to number between 30 and 50. As part of his missionary efforts, Labaka dropped gifts to the Tagaeri by helicopter.

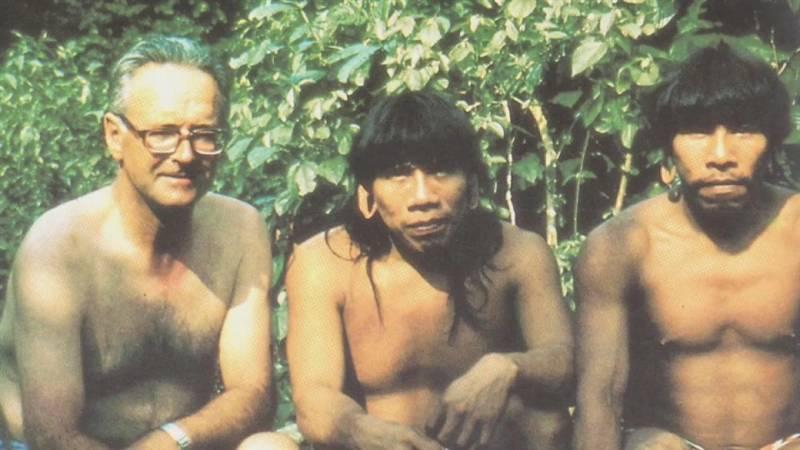

Vatican News reported that Labaka and Arango were aware of the risks of contact with the Tagaeri, yet decided to travel by helicopter to visit them on July 21, 1987. Shortly after landing in the jungle, both were savagely murdered by members of the Tagaeri, who pierced them with spears. Labaka’s body was nude when found later by fellow Capuchin José Miguel Goldáraz. Arango was still clothed, even while her veil had been removed. The Terciariascapuchinas website stated that Labaka and Arango “offered their lives for the love of the Tagaeri…”

Labaka’s Cronica Huaorana provides a first-person account of the lengths to which he and Arango went to adopt the customs and culture of the Huaorani, even to the point of living in the nude, as the natives do. In addition, an extensive biography written by Fr. Rufino María Grández, titled Vida y martirio de Mons. Alejandro Labaka y de la Hna. Inés Arango, and Tras el rito de las lanzas by former seminarian Santos Dea Macanilla, and Arango’s own Diario, provide further information about the two missionaries.

Below are excerpts that should be included in the dicastery’s considerations:

- “Blessed nudism of the Huaorani, who do not need rags to safeguard their standards of natural morality!” (Cronica Huaorani, p. 39).

- “They [the Huaorani] went naked, we began to go that way too. (…) They lived naked, and I was often naked like them too.” (Tras el rito de las lanzas: p.199-200)

- “God has wanted to preserve in these people, the way of life, the natural morality as in Paradise before sin.” (Ibid. p.57).

- As I was in my underwear, I approached the head of the family, Inihua, and Pahua, his wife; the eldest son was already beside me. With the words father, mother, sisters, family, I tried to explain to them that from now on they were my parents and siblings, that we were all one family. I knelt before Inihua, and he placed his hands on my head, rubbing my hair vigorously, indicating that he understood the meaning of the act. I did the same before Pahua, calling her “Buto bara” (my mother); she, in her role as mother, gave me a long “camachina” (advice). Then she placed her hands on my head and vigorously rubbed my hair. I stripped completely naked and kissed the hands of my Huaorani father and mother and my brothers and sisters, reaffirming that we are a true family. I understood that I had to strip myself of the old man and clothe myself more and more in Christ this Christmas. Everything took place in an atmosphere of naturalness and deep emotion, both for them and for me, without being able to guess the full commitment that this act could entail for everyone. (Cronica Huaorana. p. 37-38)

- I feared that being too rigid would be a rejection of Huaorani culture and customs; therefore, I considered it my duty to behave naturally, just like them, accepting everything except sin. Let's look at a practical example: I was left with only my clothes on, and there came a point when I couldn't stand the sweat and dirt anymore. In those circumstances, I understood that a missionary, if he has to travel through the jungle with them, must dress like them and put on clothes when the cold of the night arrives. (Ibid. p.38)

- “Missionaries should behave naturally among them; they should not be surprised by their nudity or by certain curiosities they may have with us, and we should even undress voluntarily in some circumstances, not in an exhibitionist way but so as not to create guilt complexes in a culture of extraordinary sexual maturity” (Ibid. 103).

- “Every time new missionaries join the team, the same concerns arise as in our first contacts with the Amazonian culture of the ‘naked man.’ The concern, which became almost an obsession, was that the Huaorani undressed everyone. While everyone admitted that nudity was legal within their culture, it nevertheless constituted one of the major difficulties for the entry of missionary personnel, especially religious sisters. We soon realized that the missionary should not wait to be undressed, but would do better to take the initiative to show appreciation and esteem for the culture of the Huaorani people” (Ibid. p. 144).

- “At one point, we found that the path had vanished into a deep swamp about five hundred meters long. Without hesitating for a moment, Deta (an indigenous woman) undressed and waded naked through the water up to her waist; when she reached the opposite bank, she smiled and encouraged us, while we walked cautiously, not daring to imitate her example because of our upbringing. After a couple of hours, we returned along the same path. This time, Deta didn't take off her shorts and crossed the swamp, followed by the Sisters. Shortly after, we arrived: Neñene, with her child in her arms, asked me to help her untie the drawstring of her shorts, which she then handed to me to pass to her. At this sign of trust and naturalness, I also undressed, and we crossed the swamp in this way” (Ibid. 145).

- On one occasion, when the Indian women removed the “belt” that covered their private parts, and they all ended up naked, he commented: “This is the only time that the whole group equally lived in the presence of the Creator a beautiful chapter of the Bible (Gen. 2, 25)” (Ibid., 113).

- Peigo, it seemed, was left without a hammock and approached my bed. In previous days, I had rejected him, fearing his gestures and provocative homosexual advances. This time, I had a different understanding of "accept everything except sin" and shared the bed, lying naked under the same mosquito net. This restless and rebellious leader seemed to me like a big child in need of understanding and love. In any case, he fell peacefully asleep, lulled by a prayer: "May the Lord bless us, look upon us with mercy, and deliver us from all evil. Amen. (Ibid. p. 51-52)

- I believe that, before burdening them with crucifixes, medals, and external religious objects, we must receive from them the seeds of the Word, hidden in their real lives and in their culture, where the unknown God lives. (Ibid.p.103)

- How to move from gifts to personal conversion and acceptance of the Gospel, which is the shortest path; or rather, how to overcome our immediate impatience for a real incarnation in the life of the Huao world, until we discover with them the seeds of the Word, hidden in their culture and in their lives, and through which God has shown his infinite love for the Huaorani people, giving them an opportunity for salvation in Christ. (Ibid.p. 104)

- During the first two days, we took advantage of our moments of quiet reflection to answer the questions that are often asked when we plan these visits: Why are you going to the Aucas [a derogatory term used by non-Huaorani people]? Will you be able to preach to them? What are you hoping to achieve? Quite simply: we want to visit them as brothers. It is a sign of love and deep respect for their cultural and religious situation. We want to live with them in friendship, seeking to discover with them the seeds of the Word, embedded in their culture and customs. We have nothing to say to them, nor do we presume to do so. We just want to live a chapter of Huaorani life, under the gaze of a Creator who has made us brothers. (Ibid. p. 108)

- Missionary life is not just about adaptation; above all, it is about sharing life, customs, culture, and common interests. This desire is more noticeable in them than in us, who are always influenced by the prejudices, idiosyncrasies, and taboos of our culture and religious education. (Ibid. p. 111)

- Omare and Deta invite me to join them in their recitations, with the same result of repetitions, attempts at imitation, and loud laughter. Reflecting on this personal experience with the Huaorani required me to renew my faith and hope in God, which transcends all apostolate. (...) May Christ reward, as deeds done to Him, so many signs of the goodness of the Huao people, completing them with the faith of Christ the Savior, personally accepted by them. (Ibid. p. 114)

- God wants us to enter spiritually naked. Our fundamental and priority task is to discover the “seeds of the Word” in the customs, culture, and actions of the Huaorani people; to live the fundamental truths that flourish in this people and make them worthy of eternal life. We must ask the Spirit to free us from our own spiritual inadequacy, which seeks to reach God through the Breviary, the Liturgy, or the Bible; we will have no adequate opportunity for any of that. Come, Sisters, spiritually naked, so that we may be clothed in Christ, who already lives in the Huaorani people and who will teach us the new, original, and unprecedented way of living the Gospel! (Ibid. p. 144)

- Among the Huaorani, we only want to discover Christ who lives in their culture and who reveals himself to us as Huao and Huinuni. (Ibid.p. 153)

Labaka slept in the nude with an ex-seminarian and a religious sister

In his book, Tras el rito de las lanzas, Santos Dea Macanilla relates the following episode: While in Puerto Bolívar, they gave us an unoccupied house to sleep in. Before midnight, thousands of ants arrived at this temporary dwelling; their bites don't cause much harm, but they are terribly annoying, especially at that hour, when one is peacefully resting from the previous day's work. It so happened that I was the first to notice them. Since I had packs of Full Speed cigarettes, which Father Alejandro had given me to distribute among the men who smoked wherever we arrived, I took one and blew smoke around my tent. They spread towards where Sister Inés and Father [the priest] were sleeping; after a few minutes, I saw them get up at the same time. Sister Inés was wearing a short nightgown, while Father [Alejandro] was in his birthday clothes. Sister Inés was calmly watching Father [Alejandro] pick the ants off his entire body. The next day, when I commented on it, all he said was: 'The ants surprised me, and no matter how much I looked for my shorts, which I had placed it at the head of the bed, but I couldn't find it, so I got up as I was because they were already eating me up. So, it is nothing out of the ordinary.’ And he ended with his peculiar laugh. (Tras el rito de las lanzas, p. 108).

In its deliberations about Labaka and Arango, the Dicastery for the Cause of Saints, would do well to reflect on the following found in Proverbs: “The prudent man perceives danger and seeks shelter, while the simple continue forward and pay the penalty. (27:12)